An overview of clinical diagnostic tests for sexually transmitted diseases.

Disclaimer: This article is not medical advice, any person suspecting/having contracted a venereal/sexually transmitted disease should consult with licensed medical professionals. This article is for an individual with interest in understanding the clinical diagnosis of venereal diseases.

Pathogenic microorganisms that are transmitted by human sexual behaviors infect over 1 million new people every day according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. More recently, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported an increase of cases due to COVID-19 pandemic [2]. The recent resurgence of mpox cases among sexual contacts also raises the issue whether mpox is also an STD [3]. Treatments that are meant to kill these pathogens must be tailored to specific intruders, making identification of particular pathogens crucial for disease diagnoses and the administration of appropriate therapies. Because multiple pathogens can cause similar symptoms, identification of the causative pathogen typically requires more than consultation with a physician. Rigorous microscopic and molecular methods have been developed for use by clinical microbiologists to accurately and routinely identify pathogens in human blood, serum, urine, and saliva. This article describes the most commonly used clinical microbiology testing methods, focusing on the most pervasive pathogens. This document serves only as a guide; readers should be aware of national and local standards for testing before initiating a testing regime.

Optimization of treatments requires identification of infecting pathogens. However, this is not the only reason clinical microbiologists are diligent in their methods of identification. Tracking the movement of pathogens is crucial for keeping the population healthy, and epidemiologists rely on reports from clinical laboratories and hospitals to identify potential epidemics. Moreover, identifying the presence of pathogens in human samples is important for managing supplies of donated blood and sera.

Clinical microbiology testing methods must balance sensitivity, specificity, cost, and time required.

There are inherent difficulties in identifying pathogens present in low numbers, making the sensitivity of clinical tests an issue to be considered. Many testing methods require viable microorganisms, which leads to requirements for the utmost care during collection in the clinic and subsequent transport to the laboratory. Therefore, pathogen abundance and viability must be taken into account when considering the sensitivity of diagnostic tests.

Methods used for identification are usually designed to provide the utmost specificity, so that pathogens are not mistakenly identified as present or absent. Tests must be able to distinguish pathogenic from the normal microbiota present; thus, test specificity is required for effective diagnostics.

Other considerations include budgetary constraints, as well as completing the tests in a timely manner so as to inform the treating physician.

Sexually transmitted pathogens are microbes that comprise several viruses, bacteria, and single-celled eukaryotic parasites. Bacteria and parasites typically need not to replicate within the human host cells, but viruses must, as their genomes do not encode complete machinery for nucleic acid replication and gene expression. Although these groups of microorganisms are distinct in the types of diseases they cause, and are subject to different treatments, many of the methods used to identify them overlap. For example, Abbott Alinity™ m STI Assay can detect Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) with one swab urine sample [4]. Bacteria and parasites have DNA genomes, whereas viruses may have RNA or DNA genomes. Treatments for viral venereal diseases remain challenging [5]. Table 1 summarizes the common sexually transmitted pathogens.

| Name | Type | Disease | Common method of diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Bacteria | Chlamydia | Aptima combo assay (NA-based) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Bacteria | Gonorrhoea | Aptima combo assay (NA-based) |

| Treponema pallidum | Bacteria | Syphilis | Dieterle stain (microscopy based) multiple serological tests |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Protozoan | Trichomoniasis | InPouchTV (microscopy and culture based) |

| Hepatitis B | Virus | Hepatitis | ELISA or PCR (NA-based) |

| Herpes simplex virus | Virus | Herpes | DFA or PCR |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Virus | AIDS | Ag/Ab ELISA |

| Human papillomavirus | Virus | Cervical cancer, genital warts | Microscopy of cervical smear, visual inspection, and NA-based test |

Chlamydia trachomatis is a Gram-negative bacterium that must replicate within eukaryotic cells, thus it has an obligate intracellular lifestyle. C. trachomatis causes Chlamydia, the most commonly reported sexually transmitted bacterial infection in the United States [6], with 1.7 million cases reported each year (the estimated total number of new cases is 2.86 million each year). C. trachomatis has typically been classified into serovars, based on its Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP). C. trachomatis may be identified by enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) that target the MOMP, nucleic acid (NA) recognition methods, or selective culturing. The NA recognition methods are most sensitive, and recent findings from comparative genomics have called into question the use of the MOMP for reliable diagnosis [7].

The recombinant MOMP of C. trachomatis has recently been obtained by the expression in E. coli. The purified recombinant MOMP has been applied to detect anti-C. trachomatis antibodies in patients’ sera by ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence [8]. In addition to MOMP-based tests, effective application of a cassette-enclosed Pgp3 lateral flow assay has been reported. This lateral flow assay has been described as a rapid method to detect antibodies to C. trachomatis [9].

Liang Y et al compared the efficacy of RNA-based amplification test against that of DNA-based qPCR for detection of C. trachomatis [10]. The RNA-based amplification assay showed higher sensitivity than qPCR. In addition, Harding-Esch EM et al evaluated a recombinase polymerase amplification-based prototype point-of-care test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, which has shown high sensitivity and other performance characteristics [11].

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes gonorrhea, otherwise known as "The Clap". It is estimated that over 820,000 individuals in the USA are infected with N. gonorrhoeae each year [12]. N. gonorrhoeae can be selectively cultured by growing on Thayer-Martin agar, which contains various antibiotics that inhibit other microbes. A widely used assay based on NA amplification method detects both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (discussed in Figure 4).

Another assay, which detects antimicrobial resistance determinants of N. gonorrhoeae, has recently been developed. The assay is based on mismatch amplification mutation assay-based real-time PCR and is used to identify regions associated with resistance to cephalosporins [13]. Wadsworth CB et al applied the analysis of antibiotic-responsive RNA transcripts of N. gonorrhoeae for optimization of antimicrobial susceptibility detection and identified azithromycin-sensitive transcripts using transcriptome profiling combined with reverse transcription quantitative PCR [14].

Sánchez-Busó L et al conducted a genome-based phylogeographical analysis of 419 gonococcal isolates from across the globe and found modern gonococci originated in Europe or Africa, possibly as late as the sixteenth century [15]. Venter JME et al assessed a real-time duplex PCR assay with HOLOGIC® APTIMA to detect N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis in urine and extra-genital specimens [16].

Treponema pallidum is a Gram-negative spirochaete bacterium responsible for Syphilis in over 88,000 people each year in the USA [17]. Its incidence fluctuates through time, and many recent cases appear to be transmitted between men who have sex with men [18]. Trep. pallidum can be identified using the Dieterle microscopy stain, or any one of multiple serological tests [19], in addition to NA amplification methods.

A recent study has suggested qPCR as an effective and accurate method for diagnosis of T. pallidum detection in the fixed tissue samples [20]. According to the authors, DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded samples and subjected to the conventional PCR and real-time PCR using a TaqMan® probe.

Another study evaluated the sensitivity of the rapid plasma reagin test and the serological testing combined with a 23S rRNA Trep. pallidum real-time transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) using rectal and pharyngeal swabs [21]. The combination of TMA with serological assay has been suggested to increase the sensitivity of syphilis detection.

Trichomonas vaginalis is a motile protozoan parasite that causes Trichomoniasis, occurring in an estimated 3.7 million people in the USA [22]. The most common method of diagnosis is microscopical examination and culture, both performed using the InPouch TV [23]. Diagnosis via NA amplification is becoming more common and may eventually supplant microscopy and culture [24]. Trichomonas vaginalis can produces and secretes extracellular vesicles, which facilitate the adherence of the parasite to epithelial cells in urogenital tracts [25].

In addition, Marlowe et al has compared cobas® T. vaginalis / Mycoplasma genitalium with other nucleic acid amplification tests for detecting T. vaginalis in urogenital specimens [26]. The study has found high sensitivity and specificity of cobas® TV/MG.

Hepatitis B is a DNA virus that can spread through bodily fluids, and eventually causes an inflammatory disease in the liver. This virus is becoming less prevalent, having infected only 6 individuals in 2016, compared with 3,000 individuals in the USA in 2011 [27]. Hepatitis B is often detected by testing for its antigen, or antibodies produced in response to the viral antigen [28]. As with the non-viral pathogens described above, NA amplification methods are becoming more common for detection of hepatitis B virus [29] ; however, serological testing remains the primary method of diagnosis [30].

In addition to common TA cloning-based methods, the next-generation sequencing-based method has been developed to detect pre-S mutants in the sera of HBV-infected patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [31].

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a DNA virus that causes skin lesions in the genital or oral areas. It infects approximately 776,000 individuals in the USA each year [32]. This virus can be detected using microscopy with a Tzanck smear [33], a direct fluorescent antibody, or by amplifying NA using PCR with specific primers [34]. Testing for antibodies against HSV has typically been hampered by the inability to distinguish between antibodies produced against HSV-1 (mainly oral) or HSV-2 (mainly genital); however, an immunoassay based on antibodies against glycoprotein G is promising [35].

Several molecular diagnostic tests for HSV detection in different tissues detection have recently been developed. For example, cutaneous lesions are recommended to be analyzed using Luminex ARIES HSV-1 & 2 Assay [36], while the Viper HSV-Qx test was suggested for the anogenital lesions [37]. Goux HJ et al devised a novel assay lateral-flow immunoassay (LFA) using strontium aluminate luminescent nanoparticles for the detection of HSV-2 with low cost, and high analytical and clinical sensitivity and no cross-reactivity to HSV-1 [38].

HSV can establish lifelong latency in neurons of the peripheral nervous system and cause lesions and virus shedding after reactivation. M Aubert et al evaluated gene editing through adeno-associated virus-delivered meganucleases as a treatment of latent HSV infection [39].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a DNA virus that can lead to cervical cancer in women, and genital warts in both sexes. This virus infects 14 million people each year in the USA, with an estimated total of 79 million people infected [40]. Testing for HPV relies on detection of abnormal cells near the cervix or wart structures near the genitals, performed in women during a Pap smear and cervical exam, respectively. Along with these inspections, an NA-based test is usually performed [41, 42].

In addition, GeneFirst Papilloplex® HR-HPV, a novel CE-IVD-marked real-time PCR test, has recently been introduced. The test is based on multiplex probe amplification and allows detection of 14 HPV genotypes with high reproducibility [43].

With regard to the newest methods of HPV detection, Aptima assay, one of the highly specific messenger RNA HPV diagnostic tests, is optimal for women with atypical squamous cells [44]. Furthermore, Aptima assay has been suggested for the patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [45].

Kim J and Jun SY compared the analytic efficacy of the HPV 9G DNA test vs. a peptide nucleic acid-based method (PANArray) for the detection of HPV and found that PANArray HPV was significantly more sensitive than HPV 9G DNA test [46].

Pérot P et al developed HPV RNA-seq for the detection of HPV-positive samples with similar efficacy as the standard HPV molecular diagnostic method [47]. Bik EM et al described an inclusive vaginal health assay for HPV genotyping and vaginal microbiome evaluation [48].

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has received a lot of attention throughout the years, and this is well deserved, as HIV can cause the destruction of the immune system, resulting in the inability of individuals to fight off other infections and cancerous growth. HIV infected 38,739 people in 2017 in the US, and a total of over 1.1 million people are estimated to be living with HIV [49]. HIV is an RNA virus that attaches to and infects immune cells, ultimately resulting in the death of these cells. Tests for HIV typically rely on enzyme linked immunosorbant assays (ELISAs), and although NA amplification tests have been developed, they are not as widely available or are only used when other tests are inconclusive [50].

Diagnostic methods examine organismal morphology (via microscopy), metabolism (via selective culturing), cellular macromolecules (via immunoassays), and NA sequence specificities (via amplification and/or hybridization). These tests can also be combined, for example, using a fluorescent NA probe with microscopy (Figure 1). Often times the tests are most important for distinguishing the invaders from the microbiota that normally inhabit the urogenital tract. Because viable organisms are required for several methods, the transport of clinical samples should be carefully planned. Table 2 summarizes the common diagnostic methods.

| Method | Main consideration | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Proper staining or visualization tools. | Fast, and inexpensive if the equipment is available. | Difficult to find pathogen if density is low. |

| Culture | Proper selective medium and incubation environment. | The organism in hand for additional tests (e.g., MIC). | Sample transport must ensure organisms remain viable. |

| Immunoassay | Specific antigen or antibody. | Fast, relatively inexpensive, and little equipment required. | The time between infection and antibody production may result in false negatives. |

| Nucleic acid | Specific sequence probe for hybridization or amplification priming. | High specificity and versatility. Epidemiological information can also be obtained. | Relatively expensive and time-consuming, but costs and duration are decreasing quickly. |

Pathogens can be observed either directly, or after Gram staining, or after antibody staining, under microscopes.

Microscopy is one of the oldest methods used for identification. Persons with a trained eye are able to distinguish pathogen from normal microbiota, but this is dependent on whether the density of pathogen is high enough to be seen in the examined fields of view. Examination under the microscope can be especially useful for those pathogens with characteristic morphologies, such as the spirochaete cell morphology of Trep. pallidum or the motility and relatively larger size of Trich. vaginalis.

Different microscopy methods can be used for optimal recognition. Gram stains and phase contrast microscopy can provide additional information on microbial identification.

Clinical microbiologists use tests that rely on probing a molecule that is unique to the suspected pathogen. For example, fluorescently labeled specific antibodies or NA probes may be washed over the microscope slide, tagging the pathogen with fluorescence for easy identification. The stained pathogens can be readily observed under a microscope. There are many variations of stains with antibodies or other moieties. The following is a typical process.

- obtain human samples and antibody conjugated with a fluorophore

- fix the samples to a microscope slide. Prior to fixation, it may be necessary to homogenize the sample so that it can be pipetted easily.

- fix the sample to the slide surface through air-drying, formaldehyde, or another method. Microscope slides with small wells are ideal, since a small aliquot of human sample can be placed inside the well.

- add antibody solution to the sample and incubate at a specified temperature and humidity.

- wash the slide thoroughly to remove any excess antibody, as this "loose" antibody will increase background fluorescence.

- observe under regular fluorescent or confocal microscopy.

Culturing pathogens is another old method, and is still considered as the gold standard for testing several pathogens. Culturing for identification relies on discriminating between pathogen and the background of the normal flora. If one were to simply spread sample onto a plate with a rich medium, a diversity of microbes would be able to grow. The importance of selecting only those microbes of interest has led to the development of selective culture methods, where microbiologists take advantage of microbes’ unique metabolic properties or resistances. For example, the gold standard test for Trich. vaginalis is the InPouch TV, a dual anaerobic chamber that allows microscopic examination and culturing of Trich. vaginalis in (proprietary) medium with suitable nutrients and antibiotics.

Considerations for selective culturing are the nutrients needed, antibiotics for selection, and sample isolation and streaking tools (swabs, inoculation loops, etc.).

- Identify a proper selective medium. Often these media provide nutrients that the bacteria are unable to synthesize themselves, provide a substrate for a unique metabolic process, and/or antibiotics to which the bacteria are resistant. The addition of these antibiotics is important for inhibiting the growth of the normal microbiota.

- Streak clinical sample on non-selective and selective media following a well-established protocol. Be cautious that the number of cells in the human sample may be high, and that there may be a "lawn"of growth. Sometimes it is prudent to dilute the human sample in a series of 10-fold dilutions before streaking on the agar medium.

- Incubate the streaked Petri plates. This step is critical for success, as incubation temperature, humidity, oxygen concentration, and duration all have important effects on microbial growth.

- Observe growth after an appropriate incubation period. If there is growth, sometimes a follow-up experiment for verification is required. For example, colonies may be streaked again on the same selective medium to confirm growth. Additional tests using NA hybridization or amplification would also be advised.

Culturing of viruses is possible but more complicated, as human cell cultures are required for virus reproduction [51].

Immunoassays have been widely used for the identification of many sexually transmitted pathogens, and is still the first test used for HIV testing. In these tests, clinical microbiologists are looking for molecules that indicate pathogen presence, by measuring their specific antigen; and/or looking for signs of immune system recognition of the pathogen by measuring antibody specific to pathogen antigen. Typically these immunoassays proceed by baiting the possibly present antigen in the human sample with an antibody specific to that antigen. Binding of the antibody to the antigen is detected either using fluorescence or an enzymatic reaction.

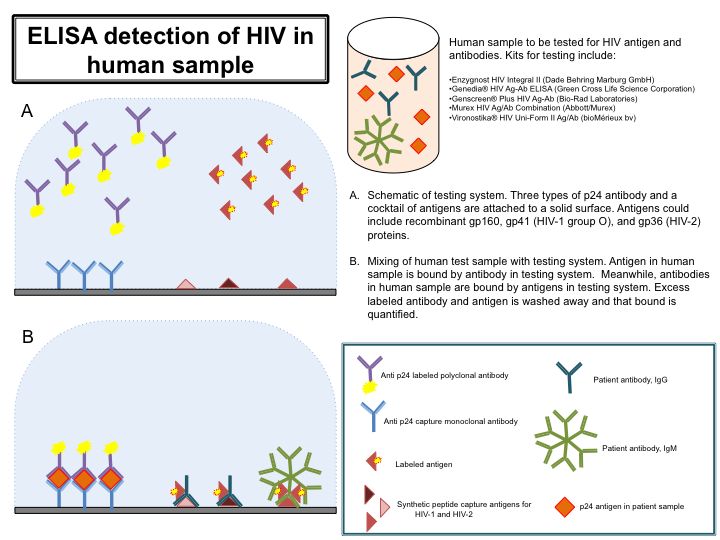

For detection of HIV infection, clinical microbiologists used an ELISA where purified HIV virus antigen was used as "bait" to test for antibodies to HIV in human blood [52]. Improvements on this test, including the use of recombinant HIV antigen, resulted in great accuracy and safety. However, because the time between HIV infection and production of antibodies can be several weeks, identification tests were further improved to include testing for HIV antigen and antibody using a combined sandwich ELISA method.

Commercial kits are available to perform these tests in an efficient and high throughput manner, and are sensitive enough to detect antibody or antigen in urine or saliva samples in addition to blood. The high throughput nature of the kits helps reduce cost in screening blood donations, and the increased sensitivity helps promote testing in developing countries, thereby improving human health globally.

- Obtain sample for testing and commercially available kit; several kits are listed in Figure 3. Follow kit instructions exactly. Figure 3 gives an overview of the ELISA process, and although each kit listed detects both antigen and antibody, they may differ in the exact method or reagents used for HIV detection.

- Monoclonal antibodies to p24, the capsid protein of HIV, are immobilized on a solid surface. Also immobilized is an antigen cocktail, with recombinant antigens representing both HIV-1 and HIV-2 strains. Also contained within the testing device are unbound labeled polyclonal anti-p24 antibodies, and unbound labeled antigen.

- An aliquot of the blood sample (often diluted) is added to the testing device. If HIV antigen is present, it will bind the anti-p24 antibodies. Similarly, if HIV antibodies are present, they will bind the labeled antigen. Wash excess label antibody and antigen from the testing device and then quantify antigen/antibody complexes by their respective labels.

Methods based on NA sequence can be some of the most sensitive, able to detect a few molecules of DNA or RNA, and are able to detect pathogens using only urine samples instead of samples from more invasive procedures (e.g., cervical or urethral swab). NA methods can have very high specificity, being able to distinguish between pathogen and normal microbiota, and even between different serovars, providing important epidemiological data along with diagnostic data. Because the presence of pathogen DNA does not necessarily indicate the presence of the viable pathogen, many NA based diagnostic tests rely on ribosomal RNA, which is also in much higher copy number than DNA, thereby increasing sensitivity. NA tests are becoming routine, and as their costs are driven down by improved technology, they are apt to become the gold standard for all diagnostic tests. NA tests where whole genomes are sequenced are even likely to become more useful in the coming years, as technology becomes less expensive [53].

NA methods rely on hybridization and/or amplification. Hybridization methods use a fluorescently labeled NA probe of known sequence to hybridize to any complementary NA present in the sample, typically using fluorescent microscopy for detection. Amplification methods use small NA primers and PCR to selectively amplify a taxonomically informative marker gene. Amplification itself can be a positive result, or subsequent sequencing of amplicons can provide additional information. The key to the specificity of hybridization and amplification methods is the fluorescently labeled probes, or primer; these are DNA fragments whose sequences should only match, and therefore bind to, the organism of interest.

Detection of nucleic acid from these two pathogens is possible using commercially available kits such as the APTIMA COMBO 2 Assay. Although the exact method and reagents used are proprietary, the steps shown in Figure 4 provide an overview of the process performed by this kit. In addition, false negatives have been noticed [54].

- Obtain a human sample for testing. From this sample, lyse any cells present so that the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is accessible.

- The freed rRNA can now bind to beads coated with a specific sequence for either Chlamydia or Neisseria, such that only rRNA from these two species will bind to the beads. The beads are then removed from the mixture of cell lysate, taking the bound rRNA with them.

- The rRNA is now used as template in a reverse-transcription reaction, where complementary DNA is synthesized from the RNA. This DNA is then used as a template in Transcription Mediated Amplification. TMA is able to make thousands of copies of the sequence tag, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the test.

- Once the TMA is finished, labeled DNA complementary to the rRNA is added. The DNA and rRNA hybrids are now labeled, and can be detected and quantified by the label bound to the DNA.

Polymerase Chain Reaction with primers specific to the organism of interest is also commonly used for the detection of pathogens. Although the cost and time required of performing PCR reaction have typically hampered the widespread adoption of PCR in clinical microbiology laboratories, technology is advancing and soon enough PCR will be cheaper and faster.

Treatment of patients suffering from bacterial infections with antibiotics requires knowledge of the resistance profile of any particular bacterial pathogen. To obtain this information, clinical microbiologists typically culture the pathogen in the presence of varying concentrations of antibiotic to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of that antibiotic. Because resistance to antibiotics evolves quickly in bacteria and can vary considerably between strains of the same species, it is important to conduct MIC tests on each isolate, even if the same species has already been tested.

For thorough guidance through the broth dilution method, readers are advised to consult references such as [55].

- Identify a rich culture medium that supports the growth of the bacteria of interest. Inoculate 4 or 5 fresh bacterial colonies from a Petri dish into a few milliliters of medium and culture overnight in the appropriate incubation environment (e.g., temperature, aeration). Multiple colonies are used to minimize the effects spontaneous mutation may have on antibiotic resistance.

- After overnight incubation, prepare a dilution series of rich medium with varying concentrations of the test antibiotic. These dilutions can be performed in test tubes, or in a 96-well plate for higher throughput. Typically it is best to dilute 2-fold serially (Figure 5). Two tubes (or wells) should remain without antibiotic; one will serve as a "no-antibiotic" control to ensure the bacteria were able to grow well in the medium and incubation conditions while the other will serve as the "no bacteria" control to ensure the medium was not contaminated.

- Once antibiotic dilution series is ready, inoculate bacteria to a final density of 5x105 colony forming units (cfu)/mL (except for the "no bacteria" control). Bacteria can be quantified using a spectrophotometer to read the optical density (OD) of the culture. OD is associated with the cfu/ml cell count and researchers should have already determined the optimal OD for reaching the required inoculum density.

From the "no antibiotic" control, plate a small volume on agar plates for enumeration of viable colony forming units. This is important to ensure that the bacteria were not inoculated at a density that was too high or low. Place agar plates and test tubes (or 96-well plate) in an appropriate incubation environment. - After overnight incubation, count colonies on agar plates and examine growth in tubes or wells to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The MIC is the lowest concentration of antibiotic where growth was not visible. Please refer to Figure 5 for additional details.

Similar to the treatment of bacterial infections with antibiotics, viral infections are often treated with antiviral drugs. Because viruses hijack human cellular machinery to replicate, choosing antiviral drugs that do not interfere with normal human cellular processes can be difficult. In addition, because viral genomes, particularly RNA genomes, have high mutation rates, resistance to antiviral drugs can evolve very rapidly. In the case of HIV, patients are usually treated with a cocktail of antiviral drugs; these cocktails typically contain at least three drugs targeting two different stages of the HIV life cycle. Because it is less likely that viruses will evolve spontaneous resistance to multiple drugs targeting separate stages of the life cycle, antiviral therapies relying on drug cocktails have extended the lives of HIV patients considerably [56, 57].

Methods used for the diagnosis of sexually transmitted pathogens are constantly changing, as new technologies are developed or optimized to deliver sensitive and specific results quickly and affordably. Methods are moving from microscopy and culture to those based on detection of proteins or NA within the pathogens.

Researchers interested in testing for these pathogens must note that governing bodies are likely to have their own set of guidelines and preferred methods, and therefore, the methods described in this article serve merely as guides for subsequent protocol development and approval. Researchers are advised to contact their local infectious disease organization for additional guidance.

Dr. Konstantin Yakimchuk added new detection methods to the pathogens in August and December 2019.

- Sexually transmitted infections STIs. Available from: www.who.int/health-topics/sexually-transmitted-infections

- STDs increased during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2022/2020-STD-surveillance-report.html

- Abbott Obtains FDA Clearance for First Test that Simultaneously Detects Four Common Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) as Cases Are on the Rise. Available from: abbott.mediaroom.com/2022-05-04-Abbott-Obtains-FDA-Clearance-for-First-Test-that-Simultaneously-Detects-Four-Common-Sexually-Transmitted-Infections-STIs-as-Cases-are-on-the-Rise

- Chlamydia - CDC Fact Sheet. Available from: www.cdc.gov/std/Chlamydia/STDFact-Chlamydia.htm

- Gonorrhea - CDC Fact Sheet. Available from: www.cdc.gov/std/Gonorrhea/STDFact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm

- Venter J, Mahlangu P, Müller E, Lewis D, Rebe K, Struthers H, et al. Comparison of an in-house real-time duplex PCR assay with commercial HOLOGIC® APTIMA assays for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in urine and extra-genital specimens. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:6 pubmed publisher

- Syphilis - CDC Fact Sheet. Available from: www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-Syphilis-detailed.htm

- Gama A, Carrillo Casas E, Hernandez Castro R, Vázquez Aceituno V, Toussaint Caire S, Xicohtencatl Cortes J, et al. Treponema pallidum ssp. pallidum identification by real-time PCR targetting the polA gene in paraffin-embedded samples positive by immunohistochemistry. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:1299-1304 pubmed publisher

- Trichomoniasis - CDC Fact Sheet. Available from: www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/STDFact-Trichomoniasis.htm

- InPouch™ TV Trichomonas vaginalis. Available from: biomeddiagnostics.com/clinical/clinical-featured/trichomonas-vaginalis

- Viral Hepatitis Statistics & Surveillance. Available from: www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2016surveillance/Table1.1.htm

- Bonino F, Chiaberge E, Maran E, Piantino P. Serological markers of HBV infectivity. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 1987;24:217-23 pubmed

- Zoulim F. New nucleic acid diagnostic tests in viral hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:309-17 pubmed

- Hepatitis B Information for Health Professionals. Available from: www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/TestingChronic.htm

- Genital Herpes - CDC Fact Sheet. Available from: www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes-detailed.htm

- Folkers E, Oranje A, Duivenvoorden J, van der Veen J, Rijlaarsdam J, Emsbroek J. Tzanck smear in diagnosing genital herpes. Genitourin Med. 1988;64:249-54 pubmed

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz R. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:737-63; quiz 764-6 pubmed

- Ashley R, Militoni J, Lee F, Nahmias A, Corey L. Comparison of Western blot (immunoblot) and glycoprotein G-specific immunodot enzyme assay for detecting antibodies to herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:662-7 pubmed

- Human Papillomavirus. Available from: www.cdc.gov/std/HPV/STDFact-HPV.htm

- HPV Cancer Screening. Available from: www.cdc.gov/hpv/screening.html

- HIV/AIDS. Available from: www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html

- 2018 Quick reference guide: Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens. Available from: stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/50872

- Busch M, Eble B, Khayam Bashi H, Heilbron D, Murphy E, Kwok S, et al. Evaluation of screened blood donations for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by culture and DNA amplification of pooled cells. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1-5 pubmed

- Jackson J, Balfour H. Practical diagnostic testing for human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:124-38 pubmed

- Materials and Methods [ISSN : 2329-5139] is a unique online journal with regularly updated review articles on laboratory materials and methods. If you are interested in contributing a manuscript or suggesting a topic, please leave us feedback.

- reagentgene

- Hepatitis B virus C

- Hepatitis B virus S

- Hepatitis B virus X

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 UL44

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 US3

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 US5

- Human alphaherpesvirus 2 US4

- Human alphaherpesvirus 2 US6

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 env

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 gag

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 gag-pol

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 nef

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 rev

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 tat

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 vif

- Human immunodeficiency virus 1 vpr

- human CD300E

method- Adeno-Associated Viral-Mediated Gene Transfer

- Antibody Applications

- Antibody Companies

- Antibody Dilution and Antibody Titer

- Antibody Quality

- Antibody Storage and Antibody Shelf Life

- Antibody Structure and Antibody Fragments

- CRISPR and Genomic Engineering

- Current PCR Methods

- Microbiome Research Methodologies

- Microscopes in Biomedical Research

- PCR Machines

- PCR Protocol and Troubleshooting

- Secondary Antibodies

- Somatic Mutations