A comprehensive review of research methods for RNA modifications / RNA epigenetics / epitranscriptomics. Also included is a comprehensive list of modified-RNA readers and enzymes involved in RNA modifications and antibodies against the readers and enzymes cited among the over 60,000 formal publications Labome has surveyed for Validated Antibody Database.

One of the basic molecules of life, the ribonucleic acid (RNA) consists of four canonical nucleobases (adenine, cytosine, guanine and uracil) linked together with ribose molecules via phosphodiester bonds. While DNA is stable and stores the genetic information that dictates the order of the nucleobases, the RNA is less stable and performs multiple roles. The messenger RNA (mRNA) transports genetic information; the transfer RNA (tRNA) carries the building blocks for protein synthesis; the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) catalyzes the formation of peptide bonds, while the long noncoding (lncRNA) or small noncoding (sncRNA) RNAs have multiple regulatory roles [2]. The four canonical bases do not have the chemical versatility required for such functions. Posttranscriptional chemical modifications introduced at specific sites increase the structural and functional diversity of RNA in all organisms [2, 3].

So far, scientists identified 163 distinct chemical modifications that were classified as [4] : i) 5-ribosyluracil or pseudouridine (Ψ), ii) simple alteration of the bases; iii) methylation of the ribose 2’-hydroxyl group (Nm); and iv) complex or hypermodifications. Ψs are the result of uridine isomerization into pseudouridine such that a C-glycosidic linkage replaces the usual N-glycosidic bond and an additional imino group becomes available for hydrogen bonding. The second and third class include simple modifications such as methylation (e.g., m3U, m7G), deamination (e.g., inosine, which has been exploited to enable RNA editing [5] ), reduction (e.g., dihydrouridine), thiolation (e.g., s2U) or alkylation (e.g., Thr-tRNA) of the base or methylation of the sugar moiety. Sequential addition of simple modifications or larger chemical groups (e.g., aromatic rings, amino acid derivatives, sugars) leads to complex modifications. Their various structures, localization, specific nomenclature and pathways of chemical synthesis are included in several databases that are updated periodically: the RNA modification database - RNAMDB [3], MeT-DB - a database of transcriptome methylation in mammalian cells [6] ; MODOMICS - a database of RNA modification pathways [7], and a database dedicated to tRNA modifications – tRNAdb [8]. Several reviews on the role of modifications in RNA are available [2, 9-12]. Multiple others were published after the emergence of the field of RNA epigenetics, also called epitranscriptomics, not only in eukaryotes [13-19], but also in bacteria [20, 21] or viruses (presumably, for example, for evading detection by human innate immunity) [22].

| Gene / UniProt | Functions | |

|---|---|---|

| YTH-family | ||

| YTHDC1 Human, Q96MU7 Mouse, E9Q5K9 | Alternative splicing regulator [23-27] mRNA splice site selection [28] Nuclear export of m6A-containing mRNAs [27] Transcriptional silencing of genes on the X chromosome [29] Involved in S-adenosyl-L-methionine homeostasis by regulating expression of MAT2A transcripts [30] | |

| YTHDC2 Human, Q9H6S0 Mouse, B2RR83 | 3'-5' RNA helicase that promotes the transition from mitotic to meiotic divisions in stem cells [24] Germline cell cycle switching [31-35] RNA processing and stability [35] Regulates the level of some m6A-containing RNAs [34] Required for spermatogenesis and oogenesis [32, 34] Involved in degradation of m6A-containing mRNAs together with the XRN1 exoribonuclease [34] | |

| YTHDF1 Human, Q9BYJ9 | Positive regulator of mRNA translation [24, 36-38] Facilitates translation initiation [39] | |

| YTHDF2 Human, Q9Y5A9 Mouse, Q91YT7; Zebrafish, E7F1H9 | Regulates mRNA stability and processing [24, 36, 39-42] Promotes cap-independent mRNA translation following heat shock stress [43] May inhibit replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) [44] Enhancer or inhibitor of KSHV gene expression and virion production [45] Promotes viral gene expression and replication of polyomavirus SV40 [46] Regulates oocyte maturation [47] Involved in hematopoietic stem cells specification [48] Key role in maternal-to-zygotic transition [49] | |

| YTHDF3 Human, Q7Z739 | Promotes mRNA translation efficiency and stability [37, 38, 50] Promotes translation of circular RNAs [50] | |

| Other YTH-domain containing proteins | ||

| Pho92 Yeast, Q06390 | Binds to the 3'-UTR region of PHO4 mRNA, decreasing its stability [51] | |

| Mmi1 Yeast, O74958 | Required for the degradation of meiosis-specific mRNAs [52] | |

| YTHDF Fruit fly, Q9VBZ5 | Role in sex determination [53] | |

| HNRNP proteins | ||

| HNRNPA2B1 Human, P22626 Rat, A7VJC2 | Packaging of nascent pre-mRNA [54] Transport of mRNAs to the cytoplasm in oligodendrocytes and neurons [55] Involved in pri-miRNA processing [56] Involved in miRNA sorting into exosomes [57] Regulator of mRNA splicing [56] Transport of HIV-1 genomic RNA out of the nucleus [58] Protects telomeric DNA repeat against endonuclease digestion [59] mRNA transport to the cytoplasm [60] | |

| HNRNPC Human, P07910 | Nucleates the assembly of 40S hnRNP particles [61] Modulates the stability and the translation of bound mRNA molecules [61-64] May play a role in spliceosome assembly and regulation of mRNA splicing [65] | |

| Other modified-RNA binding proteins | ||

| eIF3 complex Multiple subunits | Initiation transcription factor directly binds 5′ UTR m6A [66] | |

RNA modifications perform their function through two main approaches: structural changes in the modified RNA that either blocked or induce protein–RNA interactions, and direct recognition by modified-RNA binding proteins to induce subsequent reactions. Such binding proteins have been named “readers” of RNA modifications and so far only m6A readers are known. These readers are listed in Table 1. Known human enzymes modifying RNA, such as METTL3 [67], and also the human modified-RNA readers are listed in Table 2, along with research antibody information from Labome's Validated Antibody Database.

| Gene | Gene description | Top three suppliers |

|---|---|---|

| ALKBH1 | alkB homolog 1, histone H2A dioxygenase | Abcam ab195376 (1) |

| ALKBH5 | alkB homolog 5, RNA demethylase | Abcam ab195377 (2) |

| BCDIN3D | BCDIN3 domain containing RNA methyltransferase | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-390348 (2) |

| DCPS | decapping enzyme, scavenger | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-393226 (1) |

| EIF3A | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A | Cell Signaling Technology 3411 (4) |

| EIF3B | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit B | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-137214 (1), Abcam ab133601 (1) |

| EIF3F | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit F | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-390831 (1) |

| EIF3H | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit H | Cell Signaling Technology 3413 (2) |

| EIF3I | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit I | BioLegend 646701 (1) |

| EIF3J | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit J | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-376651 (1) |

| EIF3M | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit M | Dako M7157 (3) |

| FBL | fibrillarin | Cell Signaling Technology 2639 (24), Abcam ab4566 (19), Novus Biologicals NB300-269 (8) |

| FTO | FTO, alpha-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase | Abcam ab126605 (7), Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-271713 (4) |

| HNRNPA2B1 | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 | Abcam ab6102 (10), MilliporeSigma R4653 (5), Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-53531 (4) |

| HNRNPC | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (C1/C2) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-32308 (10), Abcam ab10294 (6), Invitrogen MA1-24631 (1) |

| HSD17B10 | hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 10 | Abcam ab10260 (3), Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank AFFN-HSD17B10-4D9 (1) |

| METTL1 | methyltransferase like 1 | Sino Biological 11525-MM05 (2) |

| METTL14 | methyltransferase like 14 | Abcam ab220030 (3) |

| METTL3 | methyltransferase like 3 | Abcam ab195352 (15) |

| NAT10 | N-acetyltransferase 10 | Abcam ab194297 (3), Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-271770 (1) |

| NSUN2 | NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase family member 2 | Invitrogen 702036 (2) |

| TRDMT1 | tRNA aspartic acid methyltransferase 1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-365001 (4), Novus Biologicals NB200-587 (2) |

| YTHDC1 | YTH domain containing 1 | Abcam ab220159 (1) |

| YTHDC2 | YTH domain containing 2 | Abcam ab220160 (1) |

| YTHDF1 | YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 1 | Abcam ab220162 (4) |

| YTHDF2 | YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 2 | Abcam ab220163 (6) |

| YTHDF3 | YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 3 | Abcam ab220161 (4), Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-377119 (2) |

Here I describe several techniques used to detect RNA modifications in detail. Some of them are old and are used to detect chemical modifications at single sites, but others are new and sensitive enough to allow detection and quantitation of a larger spectrum of modifications in the RNA. Several techniques for analysis of entire transcriptomes, which could reveal their overall function in an organism, are emerging. Liu Y et al measured global m6A level in mouse peritoneal macrophages through dot blot on poly(A)+ mRNA preparations with the anti-m6A antibody from Synaptic Systems ( 202003) [69]. The levels of modification on specific mRNA can be simply assessing through immunoprecipitation with, for example, an anti-m6A [70] or anti-m7G [71] antibody, and measuring the levels of mRNA. Wang L et al immunoprecipitated m6A-containing mRNAs with an anti-m6A antibody from RAW264.7 cell lysates and measured the levels of Cgas, p204, and Sting mRNAs through qPCR [70]. Interestingly, anti-m6A antibodies also recognize m6dA present in DNA molecules, which have led to false identification of m6dA DNA modifications in mammalian cells [72].

In this method, RNA templates are reverse-transcribed into cDNA by reverse-transcriptases (RTs) (Figure 1). Extended cDNA fragments are separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and their length is determined by autoradiography. Detailed protocols for RNA extraction from various organisms, oligonucleotide radiolabeling and RT reactions were previously described [73]. This method takes advantage of the inability of the reverse transcriptase to extend the DNA chain upon encountering chemical blocks in the RNA template to detect modified nucleotides [73, 74].

In contrast to other methods (HPLC, MS or direct sequencing, see below) the RT-based methods do not require large amounts of highly purified RNA. They can be directly applied to total RNA samples, the selection being done by specific annealing of radiolabeled DNA primers, a few bases 3’ of the analyzed site [73, 74]. However, the sequence of the analyzed RNA has to be known to allow selection of the appropriate oligonucleotide. The method is relatively inexpensive, as it does not require specialized equipment and training, and can be performed in any small laboratory.

One of the drawbacks of this method is that interpreting the results of reverse transcription from purified RNA can sometimes be difficult, as the enzyme is sensitive to RNA secondary structures and unwanted fragmentation of the RNA template by nucleases, which can lead to pausing of the transcriptase. This is why a control reaction with in vitro synthesized RNA can be very helpful [75]. The reverse transcriptase is also prone to stuttering that causes doubling of bands on a gel [75] and it cannot detect modifications that are too close to the 5’- or 3’- end of the RNA. Poly(A) tailing can be used to allow sequence scanning up to within a few nucleotides of the 3' terminus [76]. Some modifications can cause the enzyme to pause but not to stop unless special reaction conditions are used (e.g., 2’-O methylations can cause a stop only when the concentration of dNTPs is low) [77], or require special chemical treatment of the RNA template to cause the transcriptase to stop [73, 74, 76, 78].

Chemical groups on the Watson-Crick face of nucleobases (atoms 1, 2, and 6 for purines and 2, 3, and 4 for pyrimidines) block the base-pairing interaction with complementary bases [73]. This results in attenuation of primed reverse transcription at such sites, resulting in a stop (e.g., m1A [79], m1G [80], m2A [81], m2G [82], m3U [83] ) or pause (e.g., m6A, dihydrouridine, m4C, Nm [73] ) on sequencing gels, one residue 3' to the modified nucleobase. In contrast, small modifications at the Hoogsteen side (e.g., m5U, m5C, Ψ, inosine, m7G [73] ) allow the reverse transcriptase to read through making this method unfeasible for detection of such modifications. When modifications are bulky, performing the RT reaction at low dNTPs concentration might allow detection of a stop at some of these sites.

Several different modifications that are elusive to detection by reverse-transcription can be detected after specific chemical treatment of the RNA. So far, detection methods have been developed for some of the most common modifications encountered in cellular RNA: inosine (I), pseudouridine (Ψ), m3C, m5C, m7G, 2’-O-methylated nucleotides (Nm), dihydrouridine (D). Comprehensive reviews of such modifications and the chemical treatments necessary for their detection [74, 78], as well as detailed protocols for the detection procedures have been published recently [73, 76].

These methods can also be adapted for high-throughput analysis of the transcriptome [84]. For example, Carlile et al used the CMC(N-cyclohexyl-N′-β-(4-methylmorpholinium)-ethylcarbodiimide) treatment followed by a reverse-transcription method for Ψ-sequencing [76] together with cDNA ligation, PCR and Illumina DNA sequencing to detect Ψ in total yeast and human mRNA [84].

Detection of 2’-O-methylated sites in RNA proved to be difficult especially in low abundance and small RNAs that are 2’-O-methylated at their 3’-termini. A new version of the RT-based detection method, specific for identification of 2’-O-methylated residues, was recently developed [85]. The new method, referred to as RTL-P or Reverse Transcription at Low deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) concentrations followed by Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was described by Dong et al [85]. Briefly, purified RNA is treated with DNAse I to remove any DNA contaminant prior to RTL-P analysis, and then transcribed into cDNA by RT- reverse transcription at both low and high dNTP concentrations. At low dNTPs, the reverse transcriptase can stall one base prior to any 2’-O-methylated ribose, but it can readthrough the same methylated sites at high dNTPs. Thus, two different cDNA products are produced in the low dNTP reaction, while only one full-length product is generated by reverse transcription at high dNTPs. The cDNA products are amplified by PCR with a reverse primer specific to the 3’-end of the molecule, and forward primers specific to a region upstream (to detect a full-length product) and downstream (to detect shorter cDNA) of the predicted methylated site. The PCR products generated by the two sets of primers migrate as a double band on agarose gels. If a methylated residue is present at the predicted site, the intensity of the two bands is the same when the product from the high dNPTs reaction is amplified, and is less intense and longer when the cDNA from the low dNTPs reaction is used. There is no difference between the low and high dNTPs reactions bands when the 2’-O-methylation is missing. The same method can be used for detection of 3’-end 2’-O-methylated residues of small RNAs after ligation of 3’-end adaptors using T4 ligase [85]. Direct and site-specific quantification of RNA 2′-O-methylation by PCR can also be achieved through an engineered DNA polymerase which is able to discriminate 2′-O-methylated from unmethylated RNAs [86]. J Shi et al developed PANDORA-seq (panoramic RNA display by overcoming RNA modification aborted sequencing) to facilitate the detection of small non-coding RNA (sncRNA) with RNA modifications [87].

Identification of modified nucleotides in RNA by thin layer chromatography (TLC) is another relatively simple and inexpensive approach that can be used in any small research laboratory. Detailed reviews of the technique have been published in recent years [88, 89]. The method is very effective when applied to short RNAs (~100-150 nt) like transfer RNA or other small non-coding RNAs. Larger molecules can be analyzed after ribonuclease digestion and RNA fragments purification.

Complete digestion of RNA by various ribonucleases is required prior to analysis of the RNA digest products by 2-dimensional separation on TLC plates. The products differ depending on the nuclease used. RNase T2 digestion produces 3’-monophosphate nucleosides, both nuclease P1 and the venom phosphodiesterase (VPD) generate 5’-monophosphate nucleosides, and piperidine releases both 2’- and 3- monophosphate nucleosides. Incomplete digestions can also produce dinucleotides diphosphates. Grosjean et al developed two solvent systems for nucleosides separation and constructed reference maps for 5’- monophosphate nucleosides derived from all four nucleobases, as well as for dinucleotide diphosphates [89]. These maps indicate the relative localization of more than 70 modified nucleotides in the 2D TLC systems developed [89].

Modified nucleotides in RNA can be quantitated when 32P pre-labeled radioactive RNA [89] is used for analysis. The amount of radioactivity in each spot on the TLC plate can be determined by exposure to a PhosphorImager screen and data analysis by ImageQuant and Excel, or by direct measurement of the radioactivity in each spot after transferring the scraped plate material to a vial containing scintillation fluid followed by count measurement in a scintillation counter. Similarly, ribonuclease-digested RNA products can be radiolabeled with [90] by treatment with polynucleotide kinase prior to separation on TLC plates. Protocols for both [90] labeling approaches are available [89].

This method, either on its own or in combination with previously described methods, constitutes a powerful tool for detecting and quantifying modified nucleotides in naturally occurring RNAs [91, 92], as well as in synthetic RNA substrates treated with cell extracts or purified recombinant RNA modification enzymes [93, 94].

Several liquid chromatography (LC) methods for detection and quantitation of RNA modifications have been developed over the years [95-97]. Typically they involve purification of the RNA molecule of interest (either cold or radioactively labeled), partial or complete digestion with nucleases and phosphatase treatment prior to separation on a chromatographic column. Mono and/or oligonucleotides (or nucleosides obtained after removal of phosphate) are detected by UV absorption or measurement of radioactivity. The identification of modified nucleotides is based on differences in their chromatographic mobility when compared with their unmodified counterparts.

Nowadays reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography in conjunction with UV detection (RPLC-UV) is most often used. Gehrke and Kuo, (1989) provided a comprehensive review of such methods used for the detection and quantitation of nucleosides, either modified or unmodified, in RNAs. They include detailed chromatographic protocols, describe standard columns and the essential requirements for the HPLC instrumentation, and list chromatographic retention times and UV spectra for many ribonucleosides [98]. Mazauric et al successfully used such a method for analysis of complex RNA modifications [99].

Mass spectrometry is a very sensitive tool for detection of the mass of biological molecules. The method has been extensively used for analysis of post-translational modifications in proteins for many years [100], and it was successfully adapted to the study of modified nucleic acids [71, 101]. The principle behind these methods is simple. It involves generation of gas phase ions of the molecules of interest, either nucleosides or oligonucleotides, and separation of the generated ions according to their mass-to-charge ratios. However, the technical details of the experimental protocols can be difficult and require specialized training and equipment. Two techniques are most commonly used to generate gas phase ions: MALDI (Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization) and ESI (Electrospray Ionization).

The following experimental strategy is most commonly used for detection of modified nucleotides in RNA:

- RNA extraction. Detailed protocols for RNA extraction from different source organisms [73] as well as special considerations for RNA sample preparation for MS analysis [102] are available.

- Digestion of RNA to short oligonucleotides or nucleosides. Specific ribonucleases can be used to generate oligonucleotides of lengths suitable for mass spectrometry (about 3 to 20 nucleotides): e.g., RNase T1 [103] a guanosine-specific ribonuclease, RNase A [104] a pyrimidine-specific ribonuclease or Nuclease P1 a ribonuclease that degrades RNA molecules to nucleotides. Isolation of particular RNA fragments can also be achieved prior to nuclease degradation by site-directed hybridization followed by digestion with Mung Bean Nuclease and RNase A [103] or RNase H [105]. Full-length short RNA molecules can be used directly if they are only ~ 22 nucleotides long (miRNA, siRNA etc) [106, 107].

- Ionization of oligonucleotides or nucleosides and time-of-flight analysis to determine mass/charge ratios.

- Comparison of the experimentally determined mass/charge values with the theoretical ones based on known oligonucleotide sequence.

- Identification of modified oligonucleotides/nucleoside based on mass/charge deviations from theoretical values.

Gas phase ions generated by MALDI are singly charged ions, which are either protonated or deprotonated depending on the ion detection mode used (positive or negative). Thus the obtained mass/charge ratios correspond to the oligonucleotide mass plus or minus one hydrogen mass (1.01 Da). Due to the simplicity of the obtained spectra, MALDI can be used to determine the masses of specific molecular species within complex mixtures. However, the precise nature of the modifications cannot be obtained. Tandem MALDI-MS can be used to determine the mass and the nucleotide location of a particular modification, and whether the modification is located on the base or on the ribose, but cannot identify the exact atom at which the modification is found.

The technique can be applied to RNA fragments of about 20 nucleotides, but not mono or dinucleotides for which the mass/charge ratio signal is masked by intense noise generated from matrix and buffer components [102]. Longer RNA fragments cannot be analyzed accurately. The detection sensitivity decreases with increasing mass because of both detector design and the tendency of large RNAs molecules to fragment before detection. Also, the presence of both 12C and 13C isotopes in larger RNAs can interfere with spectra interpretation. For example, the mass difference between 13C and 12C can be interpreted as the mass difference between uridine and cytidine, about 0.98 Da [102].

Information on the exact modification site can be obtained by using tandem MS (MS/MS) to sequence the selected oligonucleotide. Tandem analysis is performed in three steps: i) Selection of the oligonucleotide of interest by setting a mass window such that all oligonucleotides of different mass are excluded from the mix; ii) fragmentation of the selected oligonucleotide by collision with an inert gas (e.g., argon); iii) mass analysis of resultant fragments followed by determination of the RNA oligonucleotide sequence and modification sites [103, 107]. Pandolfini L et al used negative ion tandem LC-MS in a hybrid quadrupole – orbitrap to identify specific m7G modification at position 11 (G11) of miRNA let-7e-5p O [71].

In spite of being such powerful tools, mass spectrometry techniques cannot easily distinguish all modifications (e.g. pseudouridines). Approaches designed for detection of pseudouridines by mass spectrometry involve selective chemical treatment [108], and were reviewed elsewhere [109]. However, due to their general chemistry (N-glycosidic bond in Us vs. C-glycosidic-bond in Ψs), uridines and Ψs have different fragmentation patterns upon collision with an inert gas. Due to these differences, a few MS-based approaches suitable for detection of Ψs without Ψ –targeted chemical treatment were also developed [110, 111].

The experimental strategy commonly used in ESI-MS experiments is essentially the same as the one used in MALDI (see above). The same steps are generally performed regardless of the ionization technique. However, a few differences between the two ionization techniques should be noted. Contrary to MALDI, ESI generates multiply charged ions that can increase the complexity of the obtained spectra especially for samples containing multiple molecular species. If the components of a complex mixture are to be identified, using ESI-MS alone is not practical as spectra interpretation can be challenging. A chromatographic separation technique is often used in conjunction with ESI-MS for such tasks (see below) [79, 112, 113]. On the positive side, ESI can be used to analyze RNAs as long as 16S rRNA (~1500 nt), and to identify the exact position of a modification within nucleotides [114].

For analysis of single nucleotides liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is the method of choice nowadays. This method relies on nuclease P1 and alkaline phosphatase digestion of RNA to nucleosides, and separation of the digestion products by reverse phase chromatography, analysis by MS and UV light (254 nm) absorption [87, 115]. Any modified nucleoside is identified on the bases of shifts in retention time from the retention times of standard nucleosides separated by the same chromatographic procedure. The UV detection indicates the stoichiometry between the modified and unmodified nucleotides, making LC-MS a great tool for quantitative analysis. Such experiments can lead to the discovery of new modifications, but localization of such modifications in the RNA species requires further studies. The most common approach relies on ribonuclease (RNase T1 or RNaseA) fragmentation of the RNA into oligonucleotides, chromatographic separation and mass spectrometry [71, 116] as described above. Most recently a 2-dimensional (2D) LC-MS method, involving the purification of nucleotides on two different liquid-chromatography columns, followed by MS-identification was developed for the analysis of modified nucleosides in biological samples [117].

The RNase H-based method is a three-step strategy for detecting and quantifying modified bases in RNA. It is most useful for the study of RNA modification enzymes than for identification of novel modifications. So far it has been successfully used for detecting 2’-O-methylated nucleotides [118], base-methylated nucleotides and pseudouridines [119].

To detect the 2’-O –methylated ribose, 2’-O-methyl RNA–DNA chimeras are used to direct RNase H cleavage in target RNA molecules [120]. RNase H selectively cleaves RNA in the formed duplex at sites were the ribose is unmodified, while any methylated ribose completely inhibits the enzyme. End-labeling and gel separation of the resulting fragments together with uncleaved, control RNA sample, reveal the methylated ribose. The level of 2’-O-methylation can be measured on the base of the intensity of the radioactive signal on the gel [118].

To detect base modifications, Zhao and Yu made several modifications to the RNase H approach (Figure 5). First, the RNA is cleaved at the 5’- side of the modified nucleotide of interest. The released products are a 5’-fragment with a 3’-hydroxyl end, and a 3’-fragment containing the phosphorylated modified nucleotide at its 5’- end. The 3’-fragment is gel purified, dephosphorylated and rephosphorylated with 32P in a reaction catalyzed by polynucleotide kinase (PNK). Finally, the fragment is digested with nuclease P1, and the released radiolabeled nucleotide at the 5’-end of the 3’-fragment is isolated and quantitated by thin layer chromatography as described above.

Similarly to the RNase H cleavage method, one can detect and quantitate RNA modifications by using a DNAzyme. The in vitro selected DNA-based enzyme consists of a small single-stranded DNA molecule with a catalytic domain of about 15 deoxynucleotides, flanked by two substrate-recognition domains of seven to eight deoxynucleotides each [121]. The DNA enzyme anneals to the RNA substrate through Watson–Crick base pairing and cleaves the target RNA at or near the site of interest, between an unpaired purine and a paired pyrimidine residue [121]. Based on their ability to digest only the unmodified substrates, DNAzymes allow the identification of ribose methylations and pseudouridines [122, 123]. Hengesbach et al describe two different approaches for the use of this method. In the first approach the substrate RNA is cleaved 5’ of the residue of interest and the digestion product is radioactively labeled prior to digestion to nucleosides and analysis by thin-layer chromatography. A more detailed description of this approach was published recently [124]. The second approach involves two DNAzyme-directed cleavages to excise RNA fragments comprising the modified nucleotides of interest, followed by RNA fragment isolation and analysis. Quantitation of modified RNA is performed by temperature cycling, iterative DNAzyme - RNA substrate complex formation and RNA cleavage [122, 124].

This method is based on molecular recognition and enzymatic ligation of DNA oligonucleotides annealed to both modified and unmodified RNA, in regions flanking specific modification sites. So far it has been successfully used to detect 2’-O-methylated nucleotides [125], m6As and pseudouridines [126].

Two oligonucleotide pairs are empirically identified. Upon ligation with T4 DNA ligase one pair can discriminate the unmodified RNA template from the modified one. The discrimination is based on the ability of the residue opposite the modification site (the recognition residue) to influence the ligation efficiency. The second pair does not distinguish between the two templates, and it is used to determine the total amount of template RNA available. Once the two sets of oligonucleotides are found, template-dependent ligation reactions are performed for each set using a mixture of modified and unmodified RNA as template.

Saika et al found several such pairs containing “recognition residues” specific to different modifications [125]. Dai et al used oligonucleotides in which they incorporated specific nucleoside analogs to introduce recognition residues specific for m6A modifications [126]. By using multiple discriminating oligonucleotide pairs, different modification sites can be analyzed simultaneously. Moreover, the relative abundance of the analyzed modifications in the RNA template can be determined on the base of the amount of ligation product detected on acrylamide gels [125, 126].

The INB method for detection of modified nucleotides in RNA was developed by combining two commonly used molecular biology techniques: Western and Northern blotting. With this method antibodies against the modified nucleotides are used for detection instead of the radiolabeled DNA probes used in the classical northern blotting protocols. Mishima et al [1] demonstrated that antibodies against 1-methyladenosine (m1A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), pseudouridine, and 5-methylcytidine (m5C) could be successfully used in various research projects. The method is relatively simple, uses commonly available laboratory equipment and has high sensitivity and specificity. It could be a great tool for studying RNA metabolism in small laboratories.

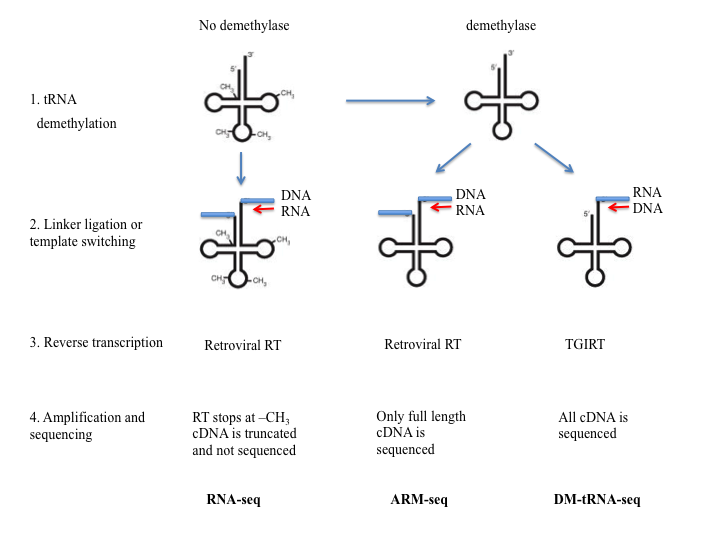

Two methods that involve removing modified nucleotides that block reverse transcriptase have been recently developed and made possible the sequencing of RNA molecules that are highly modified or folded, like tRNAs. The methods developed by Cozen et al [127] (ARM-seq) and Zheng et al [128] (DM-tRNA-Seq) use pre-treatment of RNA with Escherichia coli AlkB dealkylating enzyme to demethylate 1- methyladenosine (m1A), 3-methylcytidine (m3C), and 1-methylguanosine (m1G). The demethylated RNA together with an untreated sample is subjected to steps similar to the ones used in RNA-Seq. Adaptor ligation followed by reverse-transcription, amplification and deep sequencing were used by Cozen et al To eliminate the inefficient adaptor ligation step, Zheng et al used the thermostable group II intron reverse transcriptase (TGIRT), an enzyme that can switch the templates and allows for amplification without added adaptors.

Addepalli et al [129] used an engineered nuclease (MC1) to cleave RNA at the 5'-termini of uridine and pseudouridine, but not next to chemically modified uridine or uridine preceded by a nucleoside with a bulky modification. They identified the modified nucleotides after separating and analyzing the fragmented products by ion-pairing reverse phase liquid-chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (IP-RP-LC-MS).

Oxford Nanopore's direct RNA sequencing technology is based on a nanopore DNA sequencing technique developed recently [130, 131]. It is a direct RNA sequencing (direct RNA-seq) technology that allows the accurate quantification and characterization transcripts without fragmentation or amplification. In addition, the methodology permits the direct detection of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA modifications in endogenous molecules with high accuracy. In this method, a single strand of nucleic acids passes through a pore protein embedded in an electrically resistant polymer membrane that is subjected to an ionic current. Nanopore detects changes in the electric current as the molecules pass through it (Figure #). By interpreting the recorded electrical signals, each nucleotide in the sequence can be identified. Because the current is sensitive to base modifications any chemical modification can be detected with accuracy. As each nucleotide/modification induces a specific electrical signal, the entire nucleotide sequence can be read together with any present modifications.

Lorenz et al [132] developed and algorithm to annotate m6A in previously unknown sites containing conserved DRACH (D=G/A/U, R=G/A, H=A/U/C) motifs [133]. Choosing only DRACH sites helped improve the likelihood that the predictions are specific to m6A sites and not to other mRNA modifications. The software, called MINES (m6A Identification using Nanopore Sequencing) was trained with m6A-modified and unmodified synthetic sequences and, when tested on endogenous transcript could indicate m6A RNA modifications with high accuracy. By using data from data generated from an Oxford Nanopore sequencer as input, MINES predicted m6A modified sites in 13,000 previously unknown DRACH sites in endogenous transcripts from HEK293T cells and over 40, 000 in a human mammary epithelial cell line. In addition, by using cDNA alignments, MINES was able to predict m6A methylation in an isoform-specific manner.

Sequencing RNA is a straightforward procedure in modern-day molecular biology. Purified RNA is reverse-transcribed into cDNA prior to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and DNA sequencing. However, modifications of the RNA molecules are not easily “readable” by this method. One exception is the detection of deaminated adenosines (inosines) in mRNAs. Because inosines are decoded like guanosines, the cDNA of edited mRNA differs from the genomic DNA at A-to-I editing sites. Thus, by a simple comparison of the genomic DNA and cDNA sequences these sites can be identified [134]. More recently Ramaswami et al, developed a bioinformatics-based method to identify RNA editing sites from RNA sequencing data obtained from multiple samples, without the need for matched genomic DNA sequence [135].

The amplification-based RNA sequencing method was adapted to the detection of methylated cytosines (m5C) by treating the RNA sample with bisulfite such that cytosines established are efficiently deaminated into uridine [136-138]. Bisulfite treatment deaminates nonmethylated cytosines, while methylated cytosines remain unaffected. cDNA synthesis followed by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing allows detection and quantitation of the methylated cytosines in RNA samples.

Khoddami and Cairns developed a novel method to identify cytosines targeted by m5C methyltransferases [139]. This technique allows identification of m5C residues even in low abundance RNA species, it is applied to live cells and does not require knocking out any methyltransferase gene. Briefly, an m5C RNA methyltransferase of interested is overexpressed in living cells that are subsequently grown in the presence of 5-azacytidine (5-aza-C), a suicide inhibitor that incorporates in nascent RNAs and traps the enzyme by forming a stable RNA methyltransferase-RNA adduct. Methyltransferase specific antibodies bound to magnetic beads are then used to immunoprecipitate the formed adducts from cell lysates. Stringent washing is performed to eliminate RNA contaminants, and the remaining molecules are fragmented, released and purified. The isolated RNA fragments are ligated to adaptor oligonucleotides and reverse transcribed into cDNA that is further analyzed by DNA sequencing.

N(6)-methyladenosine-sequencing (m6A-seq), also known as MeRIP-seq, is used to localize m6A in the transcriptome at high resolution. The technique is based on RNA fragmentation and immunoprecipitation with m6A specific antibodies, followed by stringent washing and release of remaining molecules. The isolated RNA fragments are ligated to adaptor oligonucleotides and reverse transcribed into cDNA that is further analyzed by DNA sequencing. A consensus motif is found and localized in the sequence [140]. Several examples are present in the literature. Studies by Dominissini et al [40] and by Meyer et al [141] used this method to assess the m6A methylation patterns in mouse and human cells under different conditions. An improved version of the method was successfully used by Schwartz et al [142] to dissect the m6A methylation during meiosis in yeast. Even though technically they the same method their system allows for better controls, they use less starting material. They reduced the number of false positive or negative results and localized the m6As at nearly single nucleotide resolution.

miCLIP (m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation) and PA-m6A-seq (photo-crosslinking assisted m6A sequencing) are two other variations of the m6A-seq method that were recently used to map m6A at single-nucleotide resolution. Both miCLIP, developed by Linder et al [143], used by, for example, by Huang H et al [144], and PA-m6A-seq used by Chen K et al [145], involve the crosslinking of the m6A-specific antibody to the RNA prior to the affinity purification of the RNA-antibody complexes, RNA isolation, reverse-transcription and DNA sequencing.

Pseudo-seq methods that provide a comprehensive analysis of Ψ in RNA with single-nucleotide resolution have been developed during the last 2-3 years. They adapted the use of reverse-transcription after chemical modification of the RNA to high-throughput analysis of the transcriptome. For example, Carlile et al [146, 147] and Lovejoy et al [148] used the CMC(N-cyclohexyl-N′-β-(4-methylmorpholinium)-ethylcarbodiimide) treatment followed by a reverse-transcription method for Ψ-sequencing together with cDNA ligation, PCR and Illumina DNA sequencing to detect Ψ in total yeast and human mRNA (Figure 13). To map pseudouridines quantitatively, Schwartz et at [149] added a computational method through which one can determine the relative stoichiometry (Ψ-ratio) of Ψ at each identified site. Another variation of this technique, called CeU-seq [150, 151], allows for a better selection of the Ψ-containing fragments through biotin pull-down facilitated by a chemically synthesized CMC derivative.

A chemical reactivity assay to detect internal m7G in low-abundant eukaryotic RNAs, like miRNAs, was developed by Pandolfini et al [71]. The assay was based on an older method that has been used for mapping m7G residues in highly abundant RNAs and involves nucleoside hydrolysis by treatment with NaBH4 [152] and alkali, followed by aniline-induced cleavage of the RNA chain at abasic sites by β-elimination and RNA sequencing of the generated fragments. Because the fragments obtained from small RNAs cannot be easily sequenced, Pandolfini and co-authors adapted the protocol for miRNAs. In this method, decapped total RNA was treated with NaBH4 and alkali to obtain abasic sites at positions harboring m7G and exposed to a biotin-coupled aldehyde reactive probe (N-(aminooxyacetyl)-n0-(D-biotinoyl) hydrazine; ARP) able to covalently link to abasic RNA sites [153]. The linked RNA fragments were pulled down on streptavidin beads and identified from RNA libraries by high-throughput sequencing (Figure 14). Several miRNAs containing m7G were identified by this method [71]. The presence of the methylated guanidine was validated by RNA immunoprecipitation with an m7G specific antibody and qPCR analysis or RNA sequencing. A comprehensive review of RNA sequencing methods can be found here. Mass spectroscopy was used to precisely map the m7G within the small miRNA.

A major current limitation in detecting RNA modifications is the lack of methods that permit the mapping of multiple modification types simultaneously, transcriptome-wide and at single-base resolution. Khoddami et al [154] developed RBS-seq, a variant of the RNA bisulfite sequencing method to detect simultaneously m5C, Ψ, and m1A at single-base resolution transcriptome-wide. Figure 15 indicates the main steps of RBS-sequencing/mismatch-based detection of all three modifications. For m5C, bisulfite treatment deaminates Cs converting to Us (Ts upon cDNA sequencing), while methylated cytosines are do not respond to the bisulfite treatment and remain Cs. For m1A, because m1A disturbs the canonical A:T base pairing, it pauses the reverse transcriptase leading to nucleotide misincorporation. Such mismatches act as m1A signatures in the synthesized cDNA. In contrast, under the alkaline conditions of the bisulfite treatment m1A converts to m6A (methyl passes from N1 to N6) [155], which reads as A and does not induce nucleotide misincorporation (see m6A-seq method above). Comparison of bisulfite treated and untreated samples leads to identification of m1A sites. For Ψ, Ψ nucleotides upon bisulfite treatment form a stable monobisulfite adduct causing the reverse transcriptase to base skip at the pseudouridine sites.

Identifying precise modified sites in RNA transcripts is an essential prerequisite for understanding the biological functions of the modifications. Current methods allow detection of chemically modified nucleotides in most RNAs, both at specific sites and simultaneously at multiple sites. However, the modification levels can change depending upon environmental conditions or during cell differentiation. Not much information exists regarding how many RNA copies are modified. Determining such changes can be the key to understanding important biological processes. Thus, quantitative analysis methods are necessary.

The last decade provided extensive evidence for the importance of the m6A modifications in RNAs and their involvement in regulation of gene expression. Therefore, several quantitative methods were developed to quantify the m6A methylation levels of specific sites. Some are based on primer extension followed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure 1). Harcourt et al (2013) used a newly identified reverse transcriptase, Tth, that selectively incorporates thymine opposite unmodified A as compared to m6A. By performing two parallel reactions, one with Tth and one with a nonselective polymerase the authors provided a method to quantitate the amount of modified adenine at specific sites [156]. A similar approach was taken by Wang et al (2016) who provided a quantitative analysis of m6A in RNA and DNA by using BstI DNA polymerase/reverse transcriptase catalyzed primer extension [157]. The same enzyme was used in combination with PCR to quantify the m6A levels in specific residues of human SOCS1 and SOCS3 mRNAs [158], providing a simple and cost-effective method to relatively quantify the m6A levels in RNA transcripts. Most recently, Liu et al. (2020) used an IP-based commercial N6-Methyladenosine Enrichment Kit (EpiMark) to a performed m6A enrichment prior to quantification by RT-qPCR. This procedure allowed them to quantify the changes in m6A methylation level at specific target m6A sites [67].

An approach that combines primer-extension with RNase H cleavage and thin layer chromatography was used by Karijolich et al. (2010). They used RNase H to cleave only at sites where the 2′-OH of RNA is not modified to direct cleavage to a specific nucleotide of interest through the use of 2′-O-methyl RNA–DNA chimeric oligonucleotides. The cleaved RNA was radiolabeled and digested to single nucleotides that were then separated by thin layer chromatography prior to quantitation by measurement of the radioactive signal [159].

Oshima et al. (2018) used artificial nucleic acid analogs, such as bridged nucleic acid (BNA), inserted into DNA probes to increase the difference in melting temperature between m6A-RNA and unmethylated RNA during hybridization experiments (Figure 17). They applied this differential melting temperature method to determine the m6A level in rRNA in E. coli [160].

Huang et al (2019) used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) quantify the m6A abundance in poly(A) RNA to determine the role of histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation in m6A RNA modification [144]. Most recently, the same technique was used by Liu et al. (2020) to quantify the m6A/A ratio in nonribosomal chromosome associated RNAs (caRNAs) in wild type and methylase (Mettl3) or reader (Ythdc1) depleted mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). These small RNAs, whose m6A methylation state serves as a switch to regulate their levels, control the nearby chromatin state and downstream transcription [67]. The same study made use of m6A-seq, also known as MeRIP-seq (methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing) method to determine the levels of m6A in immunoprecipitated ribosomal-RNA–depleted, m6A-containing caRNAs and performed high-throughput sequencing in a methylase deficient (Mettl3) and wild type mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). The results were consistent with those obtained by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [67].

RNA-seq-based quantitative methods were also developed. Methods specific for the quantitation of ribose methylation have been recently reviewed by Krogh and Nielsen (2019) [161]. The review discusses quantitative methods for the analysis of 2’O-Me in ribosomal RNA for which the results are comparable with results obtained with other methods, emphasizing the challenges of mapping and quantitating RNA modifications especially in non-stable RNAs. More recently, L Hu et al developed a method, m6A-selective allyl chemical labeling and sequencing (m6A-SAC-seq), to measure m6A RNA modifications at single-base resolution across a transcriptome [162].

Despite the large effort and the fast progress made in the field of RNA modifications during the last few years, understanding of their functions is far from being complete. Better studied are modifications present in stable RNAs. The RNA modifications of the anticodon region of tRNAs are involved in the fine-tuning of translation. Others, outside the anticodon region, are involved in controlling the folding and stability of the molecule, or are responsible for tRNA recognition by aminoacyl synthetases [163]. Modifications of the ribosomal RNA are involved in ribosome biogenesis, function and stability, as well as in antibiotics resistance [164]. Only a few examples from messenger RNA are well described. The m7G of the 5’-cap structure of mRNA that has roles in defining the mRNA reading frame, nuclear export and splicing [165], the editing of adenosine to inosine that leads to altered base-pairing [166], and the pseudouridine of the small nuclear RNA involved in splicing [167, 168]. mRNA modifications have roles in nearly every aspect of the mRNA life cycle and various cellular processes. Proteins that add, recognize, and remove such modifications were identified and characterized, but despite the large effort and the fast progress made in the field, understanding of their functions is far from being complete [169].

A large amount of work during many years led to the development of powerful techniques that allow detection of chemically modified nucleotides in these RNAs, both at specific sites and simultaneously at multiple sites. However, good quantitative methods at base resolution and ways to simultaneously detected multiple types of modifications in the same RNA molecule or transcriptome-wide are still awaiting development.

Georgeta N Basturea added sections on BoRed-seq and RBS-sequencing in September 2019 and the section on quantitative analysis of modified RNA in February 2020.

- Pelaia P, Volturo P, Rocco M, Mille L, Malpieri R, Spinelli V. [Mechanical ventilation in hyperbaric environment: experimental evaluation of the Drager Hyperlog]. Minerva Anestesiol. 1990;56:1371 pubmed

- Harigaya Y, Tanaka H, Yamanaka S, Tanaka K, Watanabe Y, Tsutsumi C, et al. Selective elimination of messenger RNA prevents an incidence of untimely meiosis. Nature. 2006;442:45-50 pubmed

- Munro T, Magee R, Kidd G, Carson J, Barbarese E, Smith L, et al. Mutational analysis of a heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2 response element for RNA trafficking. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34389-95 pubmed

- Levesque K, Halvorsen M, Abrahamyan L, Chatel Chaix L, Poupon V, Gordon H, et al. Trafficking of HIV-1 RNA is mediated by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2 expression and impacts on viral assembly. Traffic. 2006;7:1177-93 pubmed

- Moran Jones K, Wayman L, Kennedy D, Reddel R, Sara S, Snee M, et al. hnRNP A2, a potential ssDNA/RNA molecular adapter at the telomere. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:486-96 pubmed

- Hoek K, Kidd G, Carson J, Smith R. hnRNP A2 selectively binds the cytoplasmic transport sequence of myelin basic protein mRNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7021-9 pubmed

- Huang M, Rech J, Northington S, Flicker P, Mayeda A, Krainer A, et al. The C-protein tetramer binds 230 to 240 nucleotides of pre-mRNA and nucleates the assembly of 40S heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:518-33 pubmed

- Kim J, Paek K, Choi K, Kim T, Hahm B, Kim K, et al. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C modulates translation of c-myc mRNA in a cell cycle phase-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:708-20 pubmed

- Shetty S. Regulation of urokinase receptor mRNA stability by hnRNP C in lung epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;272:107-18 pubmed

- Sebillon P, Beldjord C, Kaplan J, Brody E, Marie J. A T to G mutation in the polypyrimidine tract of the second intron of the human beta-globin gene reduces in vitro splicing efficiency: evidence for an increased hnRNP C interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3419-25 pubmed

- Motorin Y, Muller S, Behm Ansmant I, Branlant C. Identification of modified residues in RNAs by reverse transcription-based methods. Methods Enzymol. 2007;425:21-53 pubmed

- Kellner S, Burhenne J, Helm M. Detection of RNA modifications. RNA Biol. 2010;7:237-47 pubmed

- Bakin A, Ofengand J. Four newly located pseudouridylate residues in Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA are all at the peptidyltransferase center: analysis by the application of a new sequencing technique. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9754-62 pubmed

- Ofengand J, Del Campo M, Kaya Y. Mapping pseudouridines in RNA molecules. Methods. 2001;25:365-73 pubmed

- Maden B. Mapping 2'-O-methyl groups in ribosomal RNA. Methods. 2001;25:374-82 pubmed

- Kirpekar F, Hansen L, Rasmussen A, Poehlsgaard J, Vester B. The archaeon Haloarcula marismortui has few modifications in the central parts of its 23S ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:563-73 pubmed

- Gustafsson C, Persson B. Identification of the rrmA gene encoding the 23S rRNA m1G745 methyltransferase in Escherichia coli and characterization of an m1G745-deficient mutant. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:359-65 pubmed

- Toh S, Xiong L, Bae T, Mankin A. The methyltransferase YfgB/RlmN is responsible for modification of adenosine 2503 in 23S rRNA. RNA. 2008;14:98-106 pubmed

- Basturea G, Rudd K, Deutscher M. Identification and characterization of RsmE, the founding member of a new RNA base methyltransferase family. RNA. 2006;12:426-34 pubmed

- Grosjean H, Keith G, Droogmans L. Detection and quantification of modified nucleotides in RNA using thin-layer chromatography. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;265:357-91 pubmed

- Grosjean H, Droogmans L, Roovers M, Keith G. Detection of enzymatic activity of transfer RNA modification enzymes using radiolabeled tRNA substrates. Methods Enzymol. 2007;425:55-101 pubmed

- 32.

- Pintard L, Lecointe F, Bujnicki J, Bonnerot C, Grosjean H, Lapeyre B. Trm7p catalyses the formation of two 2'-O-methylriboses in yeast tRNA anticodon loop. EMBO J. 2002;21:1811-20 pubmed

- Purushothaman S, Bujnicki J, Grosjean H, Lapeyre B. Trm11p and Trm112p are both required for the formation of 2-methylguanosine at position 10 in yeast tRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4359-70 pubmed

- Roovers M, Hale C, Tricot C, Terns M, Terns R, Grosjean H, et al. Formation of the conserved pseudouridine at position 55 in archaeal tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4293-301 pubmed

- Lakings D, Gehrke C. Analysis of base composition of RNA and DNA hydrolysates by gas-liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1971;62:347-67 pubmed

- Burtis C. The determination of the base composition of RNA by high-pressure cation-exchange chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1970;51:183-94 pubmed

- Uziel M, Koh C, Cohn W. Rapid ion-exchange chromatographic microanalysis of ultraviolet-absorbing materials and its application to nucleosides. Anal Biochem. 1968;25:77-98 pubmed

- Gehrke C, Kuo K. Ribonucleoside analysis by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1989;471:3-36 pubmed

- Larsen M, Roepstorff P. Mass spectrometric identification of proteins and characterization of their post-translational modifications in proteome analysis. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 2000;366:677-90 pubmed

- Douthwaite S, Kirpekar F. Identifying modifications in RNA by MALDI mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2007;425:3-20 pubmed

- Hansen M, Kirpekar F, Ritterbusch W, Vester B. Posttranscriptional modifications in the A-loop of 23S rRNAs from selected archaea and eubacteria. RNA. 2002;8:202-13 pubmed

- Yu B, Yang Z, Li J, Minakhina S, Yang M, Padgett R, et al. Methylation as a crucial step in plant microRNA biogenesis. Science. 2005;307:932-5 pubmed

- Mengel Jørgensen J, Kirpekar F. Detection of pseudouridine and other modifications in tRNA by cyanoethylation and MALDI mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e135 pubmed

- Taucher M, Ganisl B, Breuker K. Identification, localization, and relative quantitation of pseudouridine in RNA by tandem mass spectrometry of hydrolysis products. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;304:91-97 pubmed

- Felden B, Hanawa K, Atkins J, Himeno H, Muto A, Gesteland R, et al. Presence and location of modified nucleotides in Escherichia coli tmRNA: structural mimicry with tRNA acceptor branches. EMBO J. 1998;17:3188-96 pubmed

- Kowalak J, Bruenger E, McCloskey J. Posttranscriptional modification of the central loop of domain V in Escherichia coli 23 S ribosomal RNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17758-64 pubmed

- Guymon R, Pomerantz S, Crain P, McCloskey J. Influence of phylogeny on posttranscriptional modification of rRNA in thermophilic prokaryotes: the complete modification map of 16S rRNA of Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4888-99 pubmed

- Pomerantz S, McCloskey J. Analysis of RNA hydrolyzates by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 1990;193:796-824 pubmed

- Yu Y, Shu M, Steitz J. A new method for detecting sites of 2'-O-methylation in RNA molecules. RNA. 1997;3:324-31 pubmed

- Zhao X, Yu Y. Detection and quantitation of RNA base modifications. RNA. 2004;10:996-1002 pubmed

- Lapham J, Crothers D. Site-specific cleavage of transcript RNA. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:132-9 pubmed

- Santoro S, Joyce G. A general purpose RNA-cleaving DNA enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4262-6 pubmed

- Hengesbach M, Meusburger M, Lyko F, Helm M. Use of DNAzymes for site-specific analysis of ribonucleotide modifications. RNA. 2008;14:180-7 pubmed

- Buchhaupt M, Peifer C, Entian K. Analysis of 2'-O-methylated nucleosides and pseudouridines in ribosomal RNAs using DNAzymes. Anal Biochem. 2007;361:102-8 pubmed

- Saikia M, Dai Q, Decatur W, Fournier M, Piccirilli J, Pan T. A systematic, ligation-based approach to study RNA modifications. RNA. 2006;12:2025-33 pubmed

- Dai Q, Fong R, Saikia M, Stephenson D, Yu Y, Pan T, et al. Identification of recognition residues for ligation-based detection and quantitation of pseudouridine and N6-methyladenosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6322-9 pubmed

- Eisenberg E, Li J, Levanon E. Sequence based identification of RNA editing sites. RNA Biol. 2010;7:248-52 pubmed

- Zueva V, Mankin A, Bogdanov A, Baratova L. Specific fragmentation of tRNA and rRNA at a 7-methylguanine residue in the presence of methylated carrier RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1985;146:679-87 pubmed

- Macon J, Wolfenden R. 1-Methyladenosine. Dimroth rearrangement and reversible reduction. Biochemistry. 1968;7:3453-8 pubmed

- Giege R, Sissler M, Florentz C. Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5017-35 pubmed

- Chow C, Lamichhane T, Mahto S. Expanding the nucleotide repertoire of the ribosome with post-transcriptional modifications. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:610-9 pubmed

- Materials and Methods [ISSN : 2329-5139] is a unique online journal with regularly updated review articles on laboratory materials and methods. If you are interested in contributing a manuscript or suggesting a topic, please leave us feedback.

- gene

- human ADAT1

- human ALKBH1

- human ALKBH5

- human ALKBH8

- human B5 receptor

- human BCDIN3D

- human BUD23

- human CMTR1

- human CMTR2

- human DCPS

- human DIMT1

- human DUS2

- human EIF3A

- human EIF3B

- human EIF3C

- human EIF3D

- human EIF3E

- human EIF3F

- human EIF3G

- human EIF3H

- human EIF3I

- human EIF3J

- human EIF3L

- human FA 1

- human FTO

- human HNRNPA2B1

- human HSD17B10

- human MEPCE

- human METTL1

- human METTL14

- human METTL16

- human METTL2A

- human METTL3

- human MRM1

- human MRM2

- human MRM3

- human NAT10

- human NSUN2

- human NSUN3

- human NSUN4

- human NSUN6

- human PCIF1

- human PUS1

- human PUS3

- human RNGTT

- human RNMT

- human RPUSD4

- human TFB1M

- human TGS1

- human TGT

- human TRDMT1

- human TRIT1

- human TRM5

- human TRMO

- human TRMT1

- human TRMT10A

- human TRMT10B

- human TRMT10C

- human TRMT112

- human TRMT12

- human TRMT6

- human TRMT61A

- human TRMT61B

- human TRMU

- human TYW5

- human WDR4

- human YT521

- human YTHDC2

- human YTHDF1

- human YTHDF2

- human YTHDF3

- human eIF3k

- human fibrillarin

- human hnRNP C1/C2

method- Antibody Companies

- Base Editing

- Cloning and Expression Vectors, and cDNA and microRNA Clones Companies

- Gene Knockdown Companies

- LncRNA Research Resources

- Mapping Protein-RNA Interactions by CLIP

- MicroRNA Experimental Protocols

- MicroRNA Research Reagents

- MicroRNA Research Web Resources

- Quantitative Bioanalysis of Proteins by Mass Spectrometry

- RNA Extraction

- RNA Imaging

- RNA-seq

- siRNAs and shRNAs: Tools for Protein Knockdown by Gene Silencing