An overview of Algae biofuel research methodology

As the supply of traditional, petroleum-based fuels dwindle, the need to produce viable renewable fuels increase. Other factors that motivate this research have been to reduce dependence on oil imports and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Fuel made from jatropha, rapeseed, palm, corn, and other crops have all been developed to meet the energy demand [4]. These plants must be grown on land used for traditional food crops. If all available crop land in the world were used for fuel production based on higher plants, it would still only meet less than half the world’s energy demands [5].

Microalgae have several advantages as a feedstock for biofuel. It does not require arable land, and uses less water than other crops. Microalgae can convert more than 60% of its body weight in lipids. It has been estimated that microalgae produce 15-300 times more oil than other crops based on acreage [5].

Research in biofuels using algae started with the Aquatic Species Program under the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory in the United States. In this program, many aspects of using microalgae to create biofuels were explored. Species were screened for their ability to produce lipids [6]. Over 3000 strains were screened for their suitability as a feedstock for fuels. Gene modification was conducted on microalgae cells.

Algae are a large, diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, ranging from unicellular organisms that resemble bacteria to macroscopic plant-like seaweed. Unlike true plants, even multicellular algae lack cellulose and vascular systems. They inhabit freshwater, brackish, and marine environments and even extreme environments.

Nearly all microalgae produce lipids, from 1 to 85% of biomass. Under low nitrogen conditions, a “lipid trigger” causes some algae to concentrate lipids inside their cells. This phenomenon tends to occur under low-nitrogen conditions, when nutrients have been depleted and the cells stop dividing. The lipids that microalgae produce are typically triacylglycerols, or TAG. TAG are normally converted to fatty acid methyl esters, or FAME, which are biodiesel.

Culture conditions can alter lipid content and productivity. Microalgae tend to grow more abundantly in nutrient rich water. For example, a species of Chlorella, when grown heterotrophically had a lipid content of 55% as opposed to 14% when grown autotrophically [7]. Some key species and their characteristics that make them appealing as feedstock for biofuels are listed in Table 1 [8]. Co-culturing of microalgae with other microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast, fungi, and other algae can increase the valorization [9].

| Species Name | Lipid content (% dry weight biomass) | Lipid productivity (mg/L/day) | Volumetric productivity of biomass (g/L/day) | Areal productivity of biomass (g/m2/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankistrodesmus sp. | 24.0–31.0 | 11.5–17.4 | ||

| Botryococcus braunii | 25.0–75.0 | 0.02 | 3.0 | |

| Chaetoceros muelleri | 33.6 | 21.8 | 0.07 | |

| Chlorella vulgari | 5.0–58.0 | 11.2–40.0 | 0.02–0.20 | 0.57–0.95 |

| Chlorella | 18.0–57.0 | 18.7 | 3.50–13.90 | |

| Chlorococcum sp. | 19.3 | 53.7 | 0.28 | |

| Crypthecodinium cohnii | 20.0–51.1 | 10 | ||

| Dunaliella salina | 6.0–25.0 | 116.0 | 0.22–0.34 | 1.6–3.5/ 20–38 |

| Ellipsoidion sp. | 27.4 | 47.3 | 0.17 | |

| Euglena gracilis | 14.0–20.0 | 7.70 | ||

| Isochrysis sp. | 7.1–33 | 37.8 | 0.08–0.17 | |

| Nannochloris sp. | 20.0–56.0 | 60.9–76.5 | 0.17–0.51 | |

| Nannochloropsis sp. * | 12.0–53.0 | 37.6–90.0 | 0.17–1.43 | 1.9–5.3 |

| Neochloris oleoabundans | 29.0–65.0 | 90.0–134.0 | ||

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 18.0–57.0 | 44.8 | 0.003–1.9 | 2.4–21 |

| Scenedesmus obliquus | 11.0–55.0 | 0.004–0.74 | ||

| Skeletonema costatum | 13.5–51.3 | 17.4 | 0.08 | |

| Tetraselmis sp. | 12.6–14.7 | 43.4 | 0.30 |

To screen a strain of algae, it is isolated, purified, and grown in the lab under sterile conditions. The ideal strain will have high lipid content, high growth rate, high lipid productivity, a fatty acid profile high in TAG, be able to tolerate a wide range of pH, temperatures, and salinities, be able to draw on CO2 from effluent sources, and create viable byproducts [11].

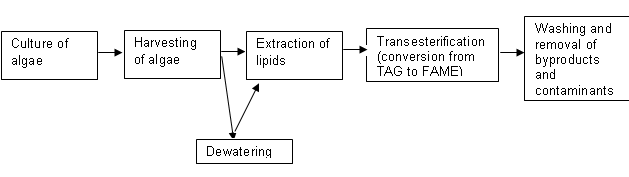

This paper reviews the methods used to create biofuels from an algae feedstock. Figure 1 diagrams the steps in the process to creating biodiesel from algae.

The culture of algae for the production of biofuels is both simple and complex. As autotrophs, they need only water and sunlight in order to live. However, in order to produce concentrations of microalgae to obtain biofuels, nutrients are required. While carbon dioxide (CO2) is provided by the air, high concentrations of CO2 can encourage higher productivity.

Media used to enhance growth of algae is a very important component of culture. Without a media containing the right ratio of nutrients, algae cannot be grown in large concentrations. Besides the macronutrients of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), other elements required for algal growth are potassium (K), calcium (Ca), sulfur (S), magnesium (Mg), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn) and zinc (Zn) [12]. Nitrogen is important for protein and carbohydrate metabolism, and when deprived of it, cell division slows and its product switches from protein to lipids. Iron is necessary for proper photosynthesis. When deprived of Mg, cells lose chlorophyll. If no S is present, cells are unable to divide [13]. In marine algae, salt (NaCl) is also important to include in media preparation. Some common media recipes are listed in Table 2.

| Media Name | Key Ingredients | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| M-8 | KNO3, KH2PO4, CaCl2, Fe EDTA, FeSO4*7H20, MgSO4*7H20 | [13] |

| Bold 3N | NaNO3, CaCl2·2H2O MgSO4·7H2O, K2HPO4, KH2PO4, NaCl, soil extract | [14] |

| Combo | CaCl2*2H20, MgSO4*7H20, K2HPO4, NaNO3, NaHCO3, Na2SiO3 9H2O, H3BO3, KCl | [15] |

| BG-11 | KH2PO4, MgSO4*7H2O, CaCl2*2H20, citric acid, Ammonium ferric citrate green, Na2 EDTA | [16] |

| f/2 | NaNO3, NaH2PO4*H2O, Na2SiO3*9H2O | [17] |

Depriving algal cells of N may cause them to concentrate lipids, but has been observed that accumulation of lipids reduces biomass production [18]. When N is decreased, other limiting factors, such as sunlight, need to be increased in order to maintain biomass [19]. Cells begin to decrease protein and increase carbohydrate content, N being essential in the synthesis of protein but not as important in carbohydrates. Photosynthesis continues at a slower rate when deprived of important macronutrients.

Since acetyl-coA carboxylase (ACCa) initiates fatty acid biosynthesis, ACCa has been overexpressed in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in order to potentiate oil accumulation [20]. Mass spectrometry analyses have revealed the significant enrichment of fatty acids in algae expressing ACCa.

Instead of using media, nutrients may be provided with commercial grade fertilizers intended for traditional crops. After the extraction of oil, the leftover biomass may be used as a fertilizer [21]. Another source of media is feedstock such as cassava [22] as feedstock. J Appl Phycol. 2010;22:573-578]. Used as a carbon source, the starchy plant cuts costs while producing high concentrations of algae. Using wastewater to feed the algae, already high in N and P, may reduce the need to add nutrients. It may lead to low lipid content unless a mixed culture is used.

Culture of algae is usually begun in the laboratory environment under sterile conditions. The first step is to obtain a pure, isolated culture of the desired strain. Algae may be sampled from the field, or ordered from a culture collection, such as University of Texas Culture Collection. The algae may then be grown in an Erlenmeyer flask and used to inoculate a carboy. In this smaller scale, artificial illumination is often used. For long term growth, algae may also be cultured on a petri dish or slant.

The effective light delivery is crucial for algae cultures. A biomimetic method for light dilution allows sufficient illumination of large reactors [23]. In particular, incorporating side-emitting optical fiber within the culture reactor has shown to significantly raise the illuminated volume and elevate the reproduction of microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis.

In addition, combining photoautotrophic cultivation with high-density fermentation has been reported to stimulate the growth of algae Scenedesmus acuminatus [24]. Moreover, growth of the algae was highly efficient when they were cultivated in photobioreactors for lipid production. Another recent study has reported the production of alkanes and alkenes by expressing light-driven oxidase from Chlorella variabilis in Yarrowia lipolytica [25]. The generated bioprocess will help to stimulate the production of hydrocarbons for different chemical applications.

In a large scale, there are two main types of reactors used to culture algae. The first is the photobioreactor, which is closed. The other type of reactor is open, usually an open pond or raceway. Both types of reactors usually have carbon dioxide injected or mixed to enhance productivity, and some type of mixing. Both also have light penetration issues. Table 3 enumerates some of the features of both types of reactors, including advantages and disadvantages, and conditions of both.

| Reactor Type | Photobioreactor, e.g., tubular or planar | Open Pond, e.g. raceway or static pond |

|---|---|---|

| Mixing | Pump | Paddlewheel |

| Light conditions | Internal illumination, control over photoperiod | Solar illumination, depth of 0.1-0.3 m to allow light penetration |

| Advantages | Control over conditions, less risk of contamination, high productivity | Less expensive, less energy intensive, utilization of local resources |

| Disadvantages | Fouling, overheating, photic dark zones | Contamination, water loss from evaporation, fluctuation of pond conditions |

| Solutions to Common Problems | Spray with water to keep from overheating | Use strains adapted to extreme conditions and batch culture to curb contamination |

| References | [26-28] | [29-31] |

In order to determine the best system for algae several factors must be considered, such as the climate, the algae to be cultured, and the nutrient resources available. A tubular PBR may be the best algal culture system in a cooler climate environment where overheating is not as much of an issue. Raceways may be more appropriate in a tropical environment near a large body of water that can feed the large amounts of water needed. There is also the option of combining a PBR and a raceway [32]. In the morning the algae could be in the PBR, and then moved to the raceway to be cooled in the afternoon. In the evening, it could return to the PBR. A PBR and an open pond could also be used for different phases in the life cycle. Nearly every pond was inoculated with the culture of a PBR [33]. At some point after a pond is inoculated, it needs to be harvested. Either the cells reach their peak, or the pond becomes contaminated. The pond should be cleaned, and then reinoculated with algae from the PBR.

A recent study described a novel microfluidic bioreactor, which was used to culture Chlorella sorokiniana [34]. The bioreactor has the controlled temperature and the adjustable illumination. Moreover, the medium components can be quickly modified. Also, the bioreactor consists of separate culture chambers, which allow the analysis at single-cell level. In addition, a comparative life cycle assessment has been presented to estimate the impact of biodiversity in algal cultures [35]. Growing algal bicultures, such as Ankistrodesmus falcatus and Selenastrum capricornutum, in outdoor ponds increased the energy return and greenhouse gas production when compared to monocultures. The results suggested that polycultures were associated with enhanced stability and biocrude parameters. Cultivation of green algae, such as Chlorella and Auxenochlorella, in bubble column photobioreactors has been characterized [36]. These photobioreactors may be applied to co-culture various algae species.

Also, a recent study has analyzed the effect of fouling control strategies for the growth of Chlorella vulgaris in a membrane photobioreactor (AMPMBR) [37]. In addition, in-situ real-time monitoring was applied to study changes of algal membrane morphology. With regard to stress-induced lipid accumulation, NaCl was used as a stress inducer to culture Chlorella sorokiniana [38]. The study has demonstrated that following the exposure to stress inducer, the algae cells interrupt their division and activate lipid synthesis.

Harvesting is a huge undertaking in the process towards a viable biofuel. It is considered the most energy intensive and expensive step in the process of creating biofuel from algae. Finding an energy efficient method is an important area of research. The methods include mechanical, chemical, and electrolytic. Harvesting methods are listed in Table 4.

| Method | Description | Materials | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centrifugation | Mechanical method that removes water by centrifugal force | Centrifuge | High recovery rate, high rate of solids, no contamination by chemicals | High energy requirement, damage to cells by shearing | [39, 40] |

| Filtration | Algae passes through membrane that retains the solids while the media passes through | Filter, suction pump | High recovery rate, lower energy requirement, no contamination by chemicals | Redilution (dewatering) may be required, fouling of filter membrane may occur | [40-42] |

| Flocculation | Aggregation of cells is caused by removing the electrostatic barrier that separates them | Flocculant, such as NaOH, chitosan, aluminum chloride | Less damaging than centrifugation, low energy requirements, efficient | Contamination of harvested algae with chemicals, hard to flocculate saltwater algae | [39, 43-45] |

| Flotation | Algae is floated to the surface using bubbling, and skimmed off the surface, often in combination with flocculation | Flocculant, gas impeller, collection bowl | No damage to cells, simple, low energy | May not work well for dense cultures | [46, 47] |

| Ultrasonic separation | Sound waves cause the cells to agglomerate | Ultrasonic wave generator, resonator chamber, pump | Removal of most water, no damage to cells, no fouling of system | High energy input, high cost, cells not as concentrated as other harvesting methods | [48] |

| Electrolytic methods | Electrodes cause coagulation of cells so that they fall out of suspension | Electrodes | Low energy input, no contamination, media can be recycled | Electrodes may foul | [41] |

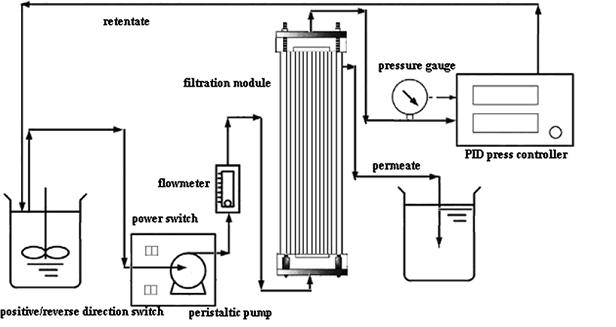

Filtration's disadvantages of fouling have been addressed in different ways. Ultrafiltration addresses the drawbacks of filtration by backwashing the membrane with saltwater in order to prevent fouling [1].

Another harvesting method solves the problems of microfiltration and flotation. By combining both of these methods, the fouling issue of filtration is solved by the bubbles of flotation. Because microfiltration is used, it concentrates the algae beyond what flotation could do [47].

Dewatering is a step that is often necessary when centrifugation or filtration is the method of harvesting, as these methods can result in a biomass that is approximately 90% water. Removing water, or drying the algae removes much of the water and concentrates the biomass. Solar drying is the least expensive method but requires a large amount of time and space [46]. Another low energy method of dewatering is to use a natural gas fired dryer [49].

Dewatering can also be performed with a bubble column [50]. Using froth flotation, algae adsorb to gas bubbles to form agglomerates. With mechanical mixing, the agglomerates become separate from the liquid. This step may be repeated in order to further concentrate the algae, and then proceed through a microfiltration membrane.

Dissolved air flotation can be used as a form of dewatering also. Combined with flocculation, this method can efficiently remove most water. Bubbles adhere to the particulates, which is facilitated by increased surface area, so flocculant is added [40]. The bubbles attached to the aggregated cells increase buoyancy and the cells rise to the surface. If the bubbles are too large, they can break up the flocs, therefore a saturation tank is used to create the correct sized bubbles for the procedure. The bubbling takes place in the flotator, and the aggregated cells are occasionally harvested.

After the cells are harvested, lipids must be extracted from the cells. In order to accomplish this, cell walls must be disrupted without extracting other components. Like harvesting, there are mechanical, chemical, and physical methods. Methods of extraction are listed in Table 5.

| Method | Description | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homogenization | Algae is expelled through small valves which disrupt the cell walls | Often used as a pretreatment for further extraction, no chemical contamination | [51] |

| Bead Milling | Algae is placed in a chamber with small beads that are agitated and disrupt cells | No chemical contamination | [28] |

| Bligh and Dyer | After determining the water content, sample is homogenized with 2:1 methanol:chloroform, and washed with chloroform and water. Two phases are formed, and the lipid phase is collected. | Not accurate with samples of greater than 2% lipid, originally designed for extraction of phospholipids of fish. | [52] |

| Folch | Algae is mixed with 2:1 chloroform:methanol, allowed to settle into phases. The lipid phase is washed and collected, and then allowed to dry. | Originally designed for extracting lipids from brain tissue. Considered the standard for lipid extraction | [53] |

| Soxhlet | A weighed sample is placed in a soxhlet apparatus, and solvent is added. The lipids are slowly extracted and then dried. | Can be a long process | [54] |

| Supercritical | A supercritical fluid is created by adding high pressure and temperature until it has properties of both. It has the density of a liquid and the compressibility of a gas. Algae is placed in an extraction vessel, and the supercritical fluid passes through the vessel and then vents to the atmosphere. | Carbon dioxide is of special interest. Temperature may be used to select for specific lipids because of its effect on solubility. | [55, 56] |

| Sonication | Bubbles are created by ultrasound, and when they burst, they disrupt cell walls. | No chemical contamination | [57] |

| Subcritical water | Water is heated to boiling, and pressure is applied, creating a solvent. | Mostly used with higher plants | [58] |

| Microwaves | Microwaves are used to generate energy in polar solvents and remove water in order to disrupt cell walls. | Rapid method | [51] |

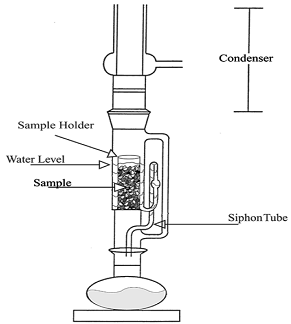

The use of solvents to extract lipids have been extensively studied since Folch and Bligh and Dyer. Usually, the cells are pretreated, often by homogenization, lyophilization, or drying, to increase efficiency of the extraction. Solvents systems include 1:1 chloroform to methanol, and usually two or more extractions are performed to remove the majority of the lipids [59]. The soxhlet method also uses solvents, as diagrammed in Figure 5. Unfortunately, most solvent methods of extraction may contaminate the finished product with unwanted chemicals. The benefit of mechanical methods is that they leave no unwanted residue.

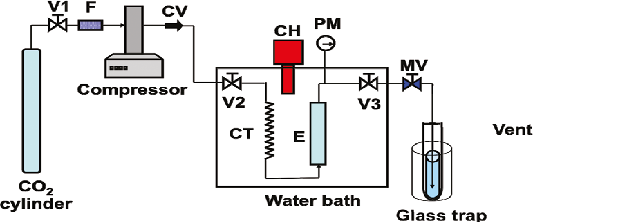

Supercritical CO2 also leaves no residue. It may be selective for non-polar bodies such as TAG. In comparison with an extraction with solvents such as hexane, yields are lower but the fatty acid profile demonstrated only non-polar lipids. This may lead to higher efficiency overall since polar lipids must be converted for biodiesel [55]. In order to perform supercritical fluid extraction with CO2, a flow-through CO2 extractor is needed. The components needed are a source of fluid, such as CO2, a pump to bring the fluid to the extraction vessel, and an extraction vessel. A compressor pressurizes and heats the fluid. The source of the fluid is either an inline cylinder or an offline container that is pumped in. A separation vessel receives the extracted lipids. A schematic of a supercritical CO2 system is illustrated in Figure 4.

Regarding the lipid isolation, a novel method of lipid using chloroform-methanol-based approach has recently been described [60]. The lipids from the chloroform fraction were mainly represented by fatty acid methyl esters, while monosaccharides sugars, acetic acid and glycerol formed the methanol layer.

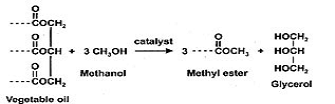

The last step in the process to creating a viable fuel is to convert the TAG to fatty acid methyl esters (FAME), the lipids that constitute diesel fuel. The process of converting TAG to FAME is known as transesterification. In this reaction, a simple alcohol such as methanol is added to lipids. A catalyst, such as NaOH, can be used. The reaction takes place in a vessel while being stirred, creating FAME and a glycerol byproduct.

If supercritical alcohol is used in the reaction a catalyst may not be necessary, and also may be used to bypass the extraction method [61]. The supercritical alcohol method is accomplished by adding methanol to dried algae and heating for 40 minutes at 90º C to cause a supercritical reaction. Mixing helps the separation process.

As in extraction, microwaves and ultrasounds can be used to assist the transesterication process. For ultrasound, 4 mL of 10:1 methanol to sulfuric acid are placed in an ultrasonic bath for ten minutes [62]. For the reaction to occur, the paste is then heated in oven at 80º C for 2 hours, and then 3 mL of hexane is added. After centrifugation, the top phase of FAME was collected and the process may be repeated to maximize FAME. With microwave extraction, microwave radiation generates heat and pressure, breaking down the cell walls. A catalyst is added to dry algae and it is irradiated [63]. The benefits of this method are a relatively simple and one-step process.

The last step in producing viable biodiesel is to remove the glycerol byproduct, along with any other contaminant that may be present. Glycerol has a density of approximately 1050 kg/m3, while biodiesel has a density of 880 kg/m3, so it can be removed via gravitational settling or centrifugation [64]. Distilled water is often used to remove most contaminants, including soap, residual catalyst, and methanol. Alkyl ester is used to dry the biodiesel and remove excess water content. Acid neutralizes the catalyst and the soap that can be formed. Then water washing is performed. Biodiesel may be washed with 10% H3PO4 and then water washed [65]. The silica gel and magnasol are used to adsorb contaminants [66]. Contaminants can be removed using a membrane [67].

Algae biomass can be used for alcohol production through a closed-loop approach, which permits to reuse cellular nitrogen for later stages of the process by transforming it into ammonium [68]. The study has described the isolation of isobutanol and isopentanol from Microchloropsis salina.

Also, Schizochitrium limacinum microalgae was the source for biodiesel synthesis using different methylating reagents, such as methanol, dimethyl carbonate and methyl acetate [69]. Methanol is required for transesterification of algae and the breaking of algal cell membranes and showed the highest reaction rates.

In order to meet the standards set by different government and international regulations, the final product must be evaluated. In Europe, the standards are EN 14214 and EN 14213; and in the United States the standard is ASTM D 6751. The variables that must be tested for in ASTM (American Standard for Testing and Materials) D 6751 are listed in Table 3 [70]. These properties of the fuel predict its viability, as well as its stability for storage and transport. These along with the fatty acid profile are normally reported for each batch of biodiesel produced.

During the transesterification procedure, the alcohol used, catalyst, glycerol byproduct, residual TAG, and free fatty acids can contaminate the final product. This is the largest source of contamination; therefore the first step in the quality control is to monitor this process.

Glycerol is the by-product of the transesterification process and should be removed. Other contaminants include free sterols, tocopherols, and sterol glucosides. These contaminants may impact fuel quality, and are usually soluble [70].

With regard to the identification of algae metabolic compounds valuable for biofuel synthesis, the lipid compounds accumulated by Parachlorella kessleri under nutrient-deprived microenvironment have recently been analyzed [71]. Nitrogen deficiency stimulated the accumulation of triacylglycerol and several metabolites, such as 2-ketoglutaric acid and citric acid, involved in the synthesis of natural lipids.

The methods of examining of chemical properties of biodiesel are listed in Table 6. The chemical compounds include the lipids, such as TAG, FAME, and the contaminants.

| Method | Description | Details | Compounds this method can evaluate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas chromatography | Sample is separated by the boiling point and polarity of compounds | Sample is dissolved, then injected into a gas chromatograph. The amount of time before the component elutes identifies it. | Fatty acid profile, methanol, glycerol, sterols, tocopherols, sterol glucosides | [70, 72] |

| Liquid chromatography | Gravity separates compounds in a solvent based on their solubility | Similar to HPLC, not considered as accurate | Combined with gas chromatography, contaminants | [72] |

| High performance liquid chromatography | Mechanical pumps separate compounds in a solvent based on their solubility | Pumps cause solvent to push the sample into a narrow column, usually packed with small dense particles. | Tocopherol, sterol glucosides | [73] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Sample molecules are ionized by an energy source. | Ions are quantified by their electrostatic acceleration and magnetic field perturbation | Fatty acid profile | [72] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance | Certain nuclei, such as 1H and 13C, are used to excite nuclear spin states of molecules | Atoms are counted in different locations in the molecule | Fatty acid profile | [74] |

| Near Infrared Spectroscopy | Infrared light has lower energy and wavelength frequency than visible light. | When infrared light is absorbed, it causes molecules to become excited so they can be identified. | Fatty acid profile | [70] |

Physical properties of biodiesel as they affect the fuel’s performance in an engine should be determined. Not all of the physical properties are required by ASTM, but are reported for the European standards (EN 14214). Table 7 lists the physical properties of biodiesel that must be reported under ASTM standards, their definitions and the standard test that is used to determine the property.

| Property | ASTM | Definition | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Gravity | Measurement of density | Tested by hydrometer | |

| Kinematic viscosity | Resistance to flow of a fluid by gravity | Measured by the time it takes for a sample of biodiesel to flow through a glass capillary tube. Kinematic viscosity= time x calibration constant | |

| Flash point | D 93 | Measure of flammability, indicates alcohol content | A sample of biodiesel is placed in a cup and heated with an external heater. A flame is passed over a cup until it reaches a flash. |

| Distillation temperature | D 1160 | Also called boiling point | The boiling point of biodiesel is high under atmospheric temperature, so it should be conducted under a vacuum. |

| Cetane number | D 613 | Has no dimensions, measurement of efficiency | While a single cylinder indirect injection engine is held at 900 rpm and intake air temperature of 150º F, the test fuel is run in the engine, and a standard ignition delay of 13º is produced. Cetane number=% n-cetane + 0.15 (%heptamethylnonane) |

| Cloud point | D 2500 | The temperature at which a cloud of wax crystals form after a liquid cools | Fuel is cooled while observed for haziness. |

| Copper strip corrosion | D 130 | Indicator of corrosive materials present in the sample | A copper strip is placed in a sample of fuel at 50º C for 3 hours, and then it is compared to a control strip. |

| Acid number | D 974 | Important factor in fuel quality | A sample of fuel is titrated using KOH in isopropanol with p-naphtholbenzein as an indicator |

| Sulfated ash | D 874 | Measurement of lubricating oils and metals it may contain | A sample of fuel is burned until ash and carbon are left. Sulfuric acid is added to remains and heated. After cooling it is repeated. The sample is then heated until its weight is constant. |

| Carbon residue | D 4530 | Measures the coking tendency of the fuel | Conradson carbon residue test. A mixed 10 g sample is placed in a crucible, which is placed in an iron crucible and then heated for 30 minutes. The sample is weighed. |

| Sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium content | UOP 391 | May lead to soap formation | Can be determined by mass spectroscopy, or inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy |

| Oxidative stability | Determines content of certain esters, effects storage of fuel | A sample of fuel is heated to 110º C while bubbling air. The rate of oxidation is observed by the sample’s conductivity. | |

| Water content | D 2709 | May be introduced during washing, and can be harmful to the fuel | Centrifugation |

| Sediment content | D 2709 | Sediment can impede the flow of fuel | Centrifugation |

Biodiesel from an algal feedstock has large potential, but there are still many opportunities for improvement. This could make an impact on the life cycle and entire process of algae to biodiesel. Since it is an energy product, reducing the energy requirements of producing biodiesel is the largest challenge. More data is needed on each step and how it affects the overall life cycle of the process. Life cycle analysis help determine energy demands for the lipid production process. This analysis is crucial to making the end product economically and energetically feasible.

Developing a system, or genetically engineering algae, that combines high biomass and lipid productivity is needed [75]. Understanding the way that algae use particular nutrients and express genes to create lipids can improve the culture of algae. Research to create a transgenic algae strain that has the desirable properties is on-going [76]. These desired traits include photosynthetic efficiency, an optimal lipid profile, thriving in extreme conditions, and concentrating lipids while still being highly productive.

More efficient and less expensive extraction methods are necessary. Since glycerol as a byproduct is created in such high numbers, it must be either safely stored or utilized to make the production of biodiesel by transesterification feasible. It is an ingredient in soap, but if biodiesel was produced in mass quantities, then using glycerol that would also be produced would effectively overwhelm the market.

The algae meal that is left after the lipids have been extracted can either be converted to sugar or fermented into ethanol [49]. This could be used in place of corn in ethanol production, and it would be cheaper and easier to produce. A recent study demonstrated that carbohydrates isolated from Euchema Spinosum could be converted into ethanol with a yield of 75% [77]. The effects of acid concentration and temperature on the hydrolysis for ethanolic fermentation have been studied. Thermal hydrolysis at 150°C has been shown to be the most efficient for alcoholic fermentation in cyanobacteria Arthrospira platensis [78]. After carbohydrates, the remaining algae meal is mostly protein. The leftover biomass can also be used for fertilizer.

Using carbon emissions to supply the algae could solve one of the requirements for algae productivity while reducing costs [79]. As well as sequestering greenhouse gas emissions it could be utilizing CO2. Using algae grown in wastewater for feedstock of fuel can also be effective in treating that same water for sanitation purposes [75]. One of the largest expenses is providing nutrients, and large amounts of nutrients, especially N and P, are crucial to productivity of algae. If wastewater could provide this nutrients while the algae fixes N, while preventing bacterial blooms. In some areas, this could provide a service by removing nitrogenous waste from water, becoming part of the sanitation system. In addition, algae have been demonstrated to be effective for heavy metals removal from wastewater. In particular, a combination of algal pond and macrophyte pond reactor has been described to efficiently remove various heavy metals, such as Cr, Pb and Zn [80].

The methods listed in this paper detail the process to creating a viable fuel from an algal feedstock. While there are numerous challenges, there is much potential in algae as source of biofuel.

Dr. Konstantin Yakimchuk updated the article in October and December, 2019.

- Grierson S, Strezov V, Bray S, Mummacari R, Danh LT, Foster N. Assessment of bio-oil extraction from Tetraselmis chui microalgae comparing supercritical CO2, solvent extraction, and thermal processing. Energy Fuels. 2012;26:248-255.

- Knothe, G. Rapid monitoring of transesterification and assessing biodiesel fuel quality by near-infrared spectroscopy using a fiber optic probe. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1999;76:795-800.

- Chisti Y. Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnol Adv. 2007;25:294-306 pubmed

- Schenk , Skye R, Hall T, Stephens E, Marx UC, Mussgnug, JH, Posten C, et al. Second generation biofuels: high-efficiency microalgae for biodiesel production. Bioenerg Res 2008; 1:20–43.

- Sheehan J, Dunahay T, Benemann J, Roessler P. A Look Back at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Aquatic Species Program – Biodiesel From Algae. Golden (CO): National Renewable Energy Institute; 1998.

- Miao X, Wu Q. Biodiesel production from heterotrophic microalgal oil. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:841-6 pubmed

- Mata TM, Martins AM, Caetano NS. Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2010;14:217-232.

- Oh-Hama T, Miyachi S. Chlorella,. In: Borowitzka MA, Borowitzka LJ, editors., Microalgal Biotechnology. Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press; 1988.

- Mandalam R, Palsson B. Elemental balancing of biomass and medium composition enhances growth capacity in high-density Chlorella vulgaris cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;59:605-11 pubmed

- Provasoli L, McLaughlin JJ, Droop MR. The development of artificial media for marine algae. Arch Microbiol. 1957;25:392-428.

- Kilham SS, Kreeger DA, Lynn SG, Goulden CE, Herrera L. COMBO: a defined freshwater culture medium for algae and zooplankton. Hydrobiologia. 1998;377:147-159.

- Stanier RY, Kunisawa R, Mandel M, Cohen-Bazire G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (Order Chroococcales). Bacteriol Rev. 1971;35:171-205.

- GUILLARD R, RYTHER J. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Can J Microbiol. 1962;8:229-39 pubmed

- Karampudi S, Chowdhury K. 2011. Effect of media on algae growth for bio-fuel production. Not Sci Biol. 2011;3:33-41.

- Lu Y, Zhai Y, Liu M, Wu, Q. 2010. Biodiesel production from algal oil using cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz.

- Ogbonna, JC, Yada H, Masui H, Tanaka H. 1996. A novel internally illuminated stirred tank photobioreactor for large scale cultivation of photosynthetic cells. J Ferment Bioen. 1996;82:61–67.

- Zijffers JW, Schippers KJ, Zheng K, Janssen M, Tramper J, Wijffels RH. 2010. Maximum photosynthetic yield of green microalgae in photobioreactors. Mar Biotechnol. 2010;12:708-718.

- Tredici MR, Materassi R. From open ponds to vertical alveolar panels: the Italian experience in the development of reactors or the mass cultivation of phototrophic microorganisms. J Appl Phycol. 1992;4:221-231.

- Borowitzka LJ, Borowitzka MA. Commercial production of β-carotene by Dunaliella salina in open ponds. Bull Mar Sci. 1990;47:244–252.

- Richmond, A. The challenge confronting industrial microalgaculture: high photosynthetic efficiency in largescale reactors. Hydrobiologia. 1987;151-152:117-121.

- Schenk , Skye R, Hall T, Stephens E, Marx UC, Mussgnug, JH, Posten C, et al. Second generation biofuels: high-efficiency microalgae for biodiesel production. Bioenerg Res 2008;1:20–43.

- Knuckey RM, Brown MR, Robert R, Frampton DM. Production of microalgal concentrates by flocculation and their assessment as aquaculture feeds. Aquacult Eng. 2006;35:300-313.

- Sim TS, Goh A, Becker, AW. Comparison of centrifugation, dissolved air flotation and drum filtration techniques for harvesting sewage-grown algae. Biomass. 1988;16:51-62.

- Uduman N, Qi Y, Danquah MK, Forde GM, Hoadley A. Dewatering of microalgal cultures: a major bottleneck to algae-based fuels. J Renewable Sust Energy. 2010;2:012701.

- Ryll T, Dutina G, Reyes A, Gunson J, Krummen L, Etcheverry T. Performance of small-scale CHO perfusion cultures using an acoustic cell filtration device for cell retention: characterization of separation efficiency and impact of perfusion on product quality. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;69:440-9 pubmed

- Tenney M, Echelberger W, Schuessler R, Pavoni J. Algal flocculation with synthetic organic polyelectrolytes. Appl Microbiol. 1969;18:965-71 pubmed

- Papazi A, Makridis P, Divanach P. Harvesting Chlorella minutissima using cell coagulants. J Appl Phycol. 2010;22:349-355.

- Divakaran R, Pillai PN. 2001. Flocculation of algae using chitosan. J Appl Phycol. 2001;14:419-422.

- Awasthi M, Singh RK. Development of algae for the production of bioethanol, biomethane, biohydrogen, and biodiesel. Int J Curr Sci. 2011;1:14-23.

- Peleka EN, Matis KA. Application of flotation as a pretreatment process during desalination. Desalination. 2008;222:1-8.

- Bosma R, Spronsen WA, Tramper J, Wijffels RH. Ultrasound, a new separation technique to harvest microalgae. J Appl Phycol. 2003;15:143-153.

- Sander K, Murthy GS. Life cycle analysis of algae biodiesel. Int J Life Cycle Ass. 2010;15:704-714.

- Guelcher SA, Kanel JS inventors; June 1999. Method for dewatering microalgae with a bubble column. United States Patent US 5,910,254.

- Mercer P, Armenta RE. Developments in oil extraction from microalgae. Eur J Lipid Sci Tech. 2011;113:539-547.

- BLIGH E, Dyer W. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911-7 pubmed

- Folch J, Lees M, SLOANE STANLEY G. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497-509 pubmed

- Bjornsson WJ, MacDougall KM, Melanson JE, O’Leary SJ, McGinn PJ. Pilot-scale supercritical carbon dioxide extractions for the recovery of triacylglycerols from microalgae: a practical tool for algal biofuels research. J Appl Phycol. 2012;24:547-555.

- King JW. Supercritical fluid extraction: present status and prospects. Gracias y Aceites. 2002;53:8–21.

- Hawthorne S, Grabanski C, Martin E, Miller D. Comparisons of soxhlet extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, supercritical fluid extraction and subcritical water extraction for environmental solids: recovery, selectivity and effects on sample matrix. J Chromatogr A. 2000;892:421-33 pubmed

- Ryckebosch E, Muyleart K, Foubert I. Optimization of an analytical procedure for extraction of lipids from microalgae. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2012;89:189-198.

- Johnson MB, Wen Z. Fuel from the microalga Schizochytrium limacinum by direct transesterification of algal biomass. Energy Fuels. 2009;23:5179-5183.

- Ho M, Probir D, Obbard, J. Determining the energy requirement for drying and optimizing the wet biomass volume to solvent ratio in one step transesterification. National University of Singapore.

- Atadashi IM, Aroua MK, Aziz AA. Biodiesel separation and purification: a review. Renew Energ. 2011;36:437-443.

- Sharma YC, Singh B. Development of biodiesel: current scenario. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2009;13:1646-1651.

- Faccini CS, da Cunha ME, Moraes MS, Krause LC, Manique MC, Rodrigues MR, et al. Dry washing in biodiesel purification: a comparative study of adsorbents. J Braz Chem Soc. 2011;22:558-563.

- Saleh J, Tremblay AY, Dubé MA. Glycerol removal from biodiesel using membrane separation technology. Fuel. 2010;89:2260-2266.

- Knothe G. Analyzing biodiesel: standards and other methods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2006;83:823-833.

- Van Gerpen J, Shanks B, Pruszko R. 2004. Biodiesel analytical methods: August 2002-January 2004. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2004;SR-510-36240.

- Knothe G. Analytical methods used in the production and fuel quality assessment of biodiesel. T ASAE. 2001;44:193-200.

- Wiley P, Brenneman K, Jacobson A. Improved algal harvesting using suspended air flotation. Water Environ Res. 2009;81:702-8 pubmed

- Doebbe A, Rupprecht J, Beckmann J, Mussgnug J, Hallmann A, Hankamer B, et al. Functional integration of the HUP1 hexose symporter gene into the genome of C. reinhardtii: Impacts on biological H(2) production. J Biotechnol. 2007;131:27-33 pubmed

- Kurano N, Ikemoto H, Miyashita H, Hasegawa T, Hata H, Miyachi S. Fixation and utilization of carbon dioxide by microalgal photosynthesis. Energ Convers Manage. 1995;36:689-692.

- Materials and Methods [ISSN : 2329-5139] is a unique online journal with regularly updated review articles on laboratory materials and methods. If you are interested in contributing a manuscript or suggesting a topic, please leave us feedback.